2D CAD in a 3D World

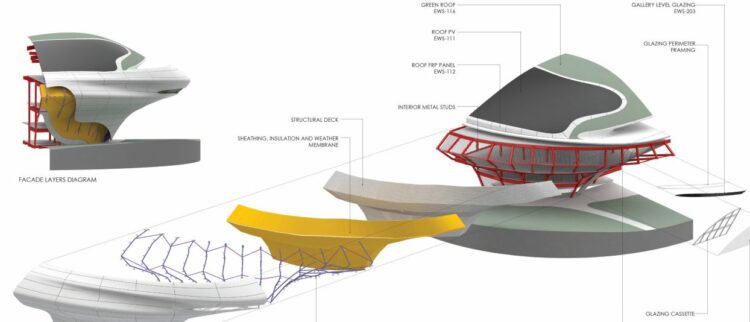

The complex wall structure is shown in an exploded axonometric drawing. (Stantec and Walter P . Moore)

There’s little doubt dawn is breaking on the brave new world of 3D modeling, BIM, reality capture, real-time rendering, simulation and digital twins for the construction industry. It’s exciting to be working in this industry when these technologies are beginning to make real impacts on the safety, productivity and efficiency of construction projects around the world. Projects that otherwise would be impossible to design, let alone fabricate and construct, now are under construction or have been completed with stunning results.

“The Lucas Museum of Narrative Arts is a great example of what can be done with 3D modeling,” explains Joe Cliggott, AIA, practice leader and principal for Stantec Architecture. “The undulating form results in a different wall section every 5 feet. Using only 2D, we’d never be able to conceive, fabricate and assemble that project.”

3D design and drafting tools certainly help make the previously impossible possible. But a project such as the Lucas Museum is exceptional; and for every complex museum or multibillion-dollar airport or stadium, there are literally thousands of home renovations, retail shopping malls, local roads and sewer-replacement projects for which 2D tools are just right for the job. “Absolutely we use 2D CAD,” says Cliggott. “Every day.”

While much of the news about industry technology tends to focus on the wonders of 3D (this publication being no exception; read our latest article on digital twins at bit.ly/3vQCyYZ), 2D drafting, design and review tools still are workhorses of the AEC industry.

“We use 2D CAD on 100 percent of our projects,” says David Garrigues, engineering and design solutions manager with civil engineering firm Kimley Horn Associates.

Donnie Gladfelter, design technology manager with Timmons Group, agrees, “80 percent of what we do is in 2D, even when we’re using our 3D software.”

It’s obvious architects, engineers, contractors, reviewers and more all make daily use of 2D plans and drawings, but why? Why, after 40 years, is Autodesk’s flagship 2D AutoCAD still a top seller? Why do software developers such as Vectorworks, Allplan and Bentley create, maintain and enhance their own 2D design and drafting offerings? Why, after nearly 20 years, is the PDF editor from Bluebeam still massively popular?

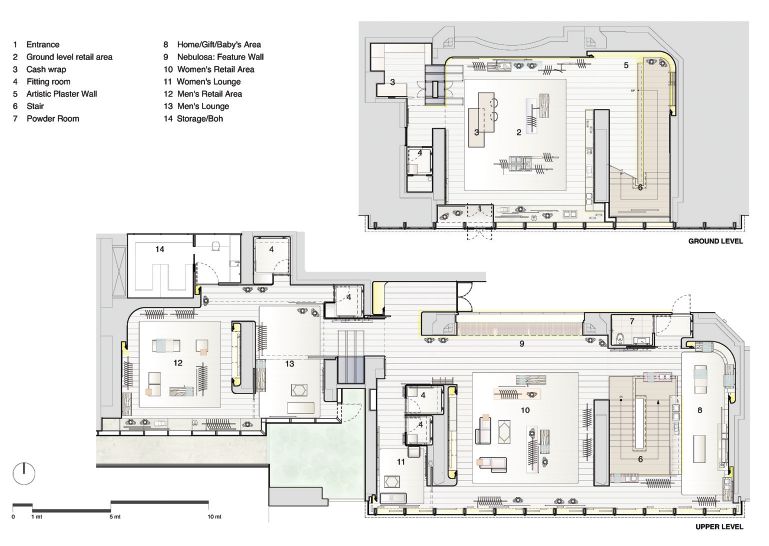

(Gabellini Sheppard Associates)

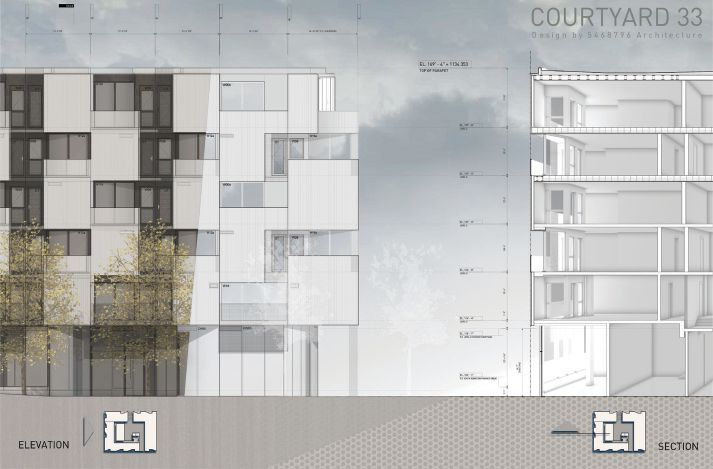

Images show a colorized plan (top) and section (bottom) views in Vectorworks.

2D’s Persistence

There are many reasons why there’s a market for products dedicated to supporting the creation, editing and viewing of 2D construction documents. They include the long legacy of 2D drawings (arguably dating back hundreds if not thousands of years), and, more recently, entrenched CAD workflows and standards, decades of industry workforce experience, and familiarity with the format.

“Most of our clients are still using 2D CAD, legacy drawings, systems and so on,” explains Cliggott. “Because all their standards are based on 2D, there is less incentive for us to move to 3D.”

This also is true, in general, of design principals, project managers and others who grew up in the industry with 2D CAD and now are senior designers or drafters and/or manage others: they’re using 2D because they’re proficient with the software and, as decision-makers for the firm, they’re less motivated to undertake the transition to 3D.

“It’s quicker for them [principals and project managers] to use 2D because they’ve been using it for 25 years,” posits Cliggott. “When will they need to jump to 3D? The inhibition to move from 2D to 3D will be generational—as 2D users retire, 3D will become more prevalent.”

Dan Istvan, vice president of the Americas for Allplan, agrees. “A primary reason 2D usage persists is familiarity with the existing tools and the trust [firms] have developed in their 2D system of standards,” he says.

And it’s not only the designers who have deep familiarity with 2D construction documents. “Contractors know 2D,” says Simon Slater, senior vice president of the Americas for Allplan. “They also often have limited onsite access to 3D models and therefore need paper [plans].”

Another reason 2D persists is the large effort required to retool for 3D, including computer systems modifications, workforce training and development of new standards. “Most companies’ and DOTs’ standards are based on 2D,” says Istvan. “Changing workflows, software and hardware is a daunting task.”

Luc Lefebvre, OAQ, LEED AP, product marketing manager, architecture, with Vectorworks, agrees, “Continued use of 2D or moving to 3D is heavily dependent on the economic size of the market and project types, such as interiors or residential architecture,” he notes. “Firms serving smaller markets or specializing in these specific types of projects are very familiar with 2D and have no need to change well-established 2D workflows.”

While these are compelling explanations for 2D’s continued ubiquity in our industry, the primary reason is that contractual agreements and municipal codes require submission of 2D plans. “The vast majority of reviewing agencies want 2D PDFs (which have absolutely taken over the function of what paper once did),” says Garrigues. The reason, he believes, is because of PDF’s consistent format. “The plans will be in the same state the reviewer left them when they return. Access to the information is consistent and fast. In 2D, it’s right there. In 3D, you must use the software interface to access the design to get the information.”

Review agencies are not alone in requiring 2D drawings. “[The] contractual obligations of the architect haven’t changed in more than 10 years,” says Lefebvre. “We are still required to create and consume 2D [PDFs]. And when 3D is required by contract, the language around the requirements is often very vague and can create a liability issue that most want to avoid.”

Let’s suppose for a moment we can flip a magic switch and upgrade the entire industry such that the supporting infrastructure for 3D is on par with that which exists for 2D. Would there still be a place for 2D drawings? “Absolutely,” says Cliggott.

2D Earns its Keep

What are the inherent advantages to using 2D CAD, specifically in the AEC industry, that allow it to stubbornly refuse to make room for more-advanced 3D tools? Actually, there are several, according to experienced industry professionals. The first relates to the ease of communicating design intent.

“At the Lucas Museum, there is much value in 3D modeling the walls to convey what is to be fabricated and constructed,” says Cliggott. “However, there is almost no value in modeling all the elements of a typical wall section for a typical building. Modeling all the details for all the walls would result in unmanageably large files. A 2D wall section, on the other hand, easily and efficiently conveys the information needed to bid on and construct the wall.”

Similarly, the simplicity of 2D hand sketches brings out the artistic component of architectural design, providing the means to communicate in the “language of drawing,” explains Vectorworks’ Lefebvre. “The drawing aspect of 2D is simple and efficient, even though it lacks the power of the underlying data associated with 3D,” he notes. “In 2D, it’s very quick for drafting, and we have better control of the graphical output.”

The ease of design creation and documentation also is a prevailing reason for the continued use of 2D in civil engineering and site design. “Most of our land-development projects are brownfield projects,” says Timmons’ Gladfelter. “The site planning is based on 2D elements like property lines, rights-of-way, setback lines and so on. Setbacks in most municipal codes are based on 2D offsets. 3D doesn’t add anything at this stage of the design and drafting process.”

2D design and drafting commonly is used for most site-development tasks, including site-geometry layout; roadway alignments; parking and roadway striping; walks, driveways and other paved surfaces; landscaping plans; and more. “With the exception of corridors, surfaces and pipes, we use 2D for everything,” says Gladfelter.

Kimley Horn’s Garrigues agrees. “For many tasks [in site development], 2D is faster and lighter to carry around,” he notes. “It’s more consumable. The 2D methods might be antiquated, but they are still faster and more efficient than other options.”

Another inherent advantage of 2D documentation is the preservation of the design at a specific point in time in a way that can be tricky with 3D models. “A 2D [plan] has traditionally been the builder’s go-to format,” says Don Jacob, vice president of technology and innovation for the Build Division, Nemetschek, makers of Bluebeam Revu PDF editor. “There’s a good reason for that. 2D plans are a snapshot in time to convey key pieces of information. The contractor only sees the information the designer intends for them to see.”

Jacob further explains that, in general, 3D models give huge advantages in terms of information conveyance, but sometimes a specific signal gets lost in the static of too much information. “An aspect of 2D drawings and PDFs is that they are a very efficient method of conveying specific information,” he adds. “The inherent value in 2D drawings is the efficient manner in which the drawing itself conveys that specific information for the intended user of that information.”

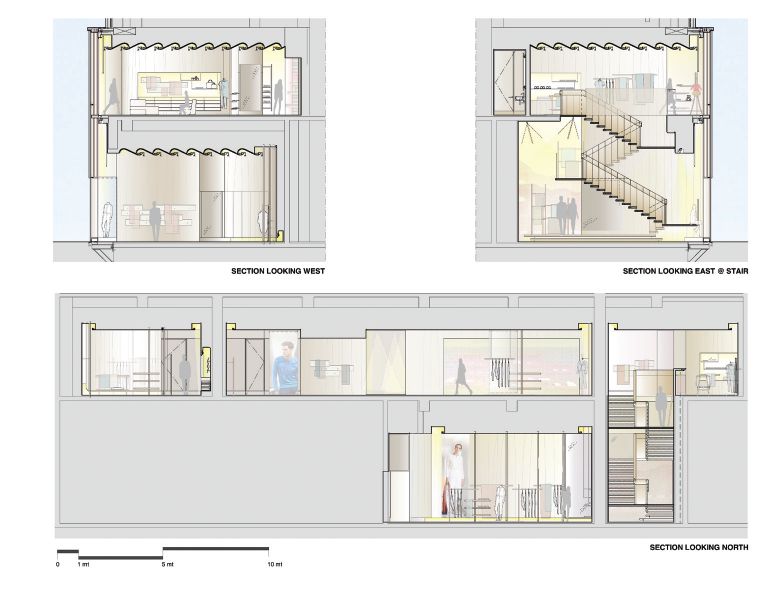

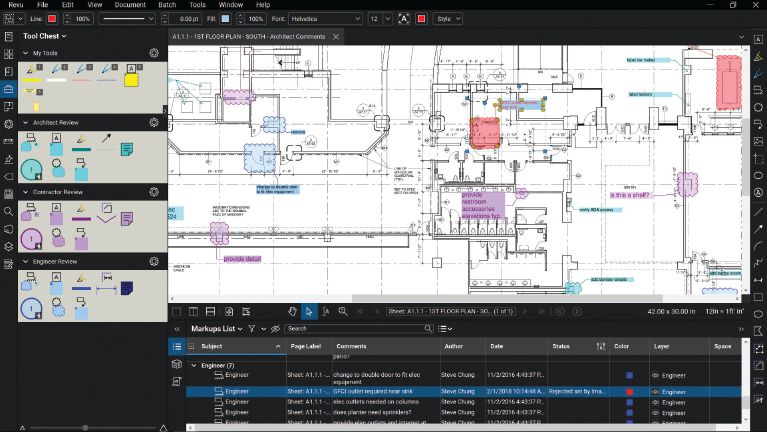

Mechanical drawings are overlaid on architectural drawings in Bluebeam Revu.

2D, 3D and Data Accessibility

With 2D’s large trained user base, existing systems and standards, and intuitive ease of use on one side, and 3D’s much-discussed benefits on the other, choosing one or the other seems like a no-win choice: select one and you forfeit the benefits of the other. However, reality is too nuanced to be reduced to a “this or that’’ choice.

Garrigues summarizes the “choice” between 2D and 3D with an analogy. “2D and 3D are like two of your children; both have positive and negative characteristics that do not necessarily compete against each other. Of course, they also might not always complement each other, either.”

The tools used depend on what the client needs throughout the lifecycle of the entire project, from concept to operations. “The needs of the owner of a factory are very different from those of a residential subdivision developer,” explains Garrigues. “A 3D model or twin of the factory is important to the owner because the goal is to not only build the facility, but also to operate and maintain that facility for a long time. On the other hand, frequently the subdivision developer’s interest ends when the new improvements are turned over to the municipality (roads, utilities, etc.), the homeowners’ association (HOA) (open spaces, detention facilities) and the individual homeowners. For these projects, there is little value in a full 3D model to the developer, and if there is no reason to spend the client’s money on the task, why do it?”

Of course, the municipality and HOA may find long-term value in 3D models of the improvements, but someone must fund the model creation. The best solution usually lies somewhere in between. Like many other firms, “we model the ground surfaces and underground utilities in 3D for the added value we get internally (for example, checking for utility conflicts; too-steep or too-flat ground slopes; etc.) and for the added value during construction,” explains Garrigues. “Given the choice, we’d prefer to create data in 3D and share in 2D. Constraints imposed by clients, technology, time and budget typically dictate our choice of tools.”

“There definitely are legitimate uses for 3D designs and models,” says Gladfelter. “HVAC contractors, steel erectors and facility managers all benefit tremendously from 3D. There is also a large percentage of projects, like residential decks, flower beds, shed permits and plats of subdivisions that only need 2D drawings.”

And then there are the in-between projects, with some elements best addressed with 3D and other elements where 2D is the preferred tool. The challenge then becomes working on a platform that can accommodate both.

Bluebeam’s Jacob concurs, “Often, the 2D/3D question is pitched as an ‘either or’ decision, but to me it’s more of an ‘and.’ Creating and sharing designs via construction documents and models is really about the data, enabling communication among all team members, and easing access to the data in whatever form is easiest for someone to digest.”

Even the simplest projects create copious amounts of data—costs, quantities, forces, geospatial relationships, schedules, products, ownership of tasks, and so on— must be documented, conveyed and interpreted by a wide audience. 2D drawings and 3D models are not the design, but rather the expression of the design. CAD and BIM applications both are just the tools we use to go from ideation to realization, for capturing and transferring this information, and recording conversations around this information.

“2D and 3D are two views of the same animal, with 2D providing the best interpretation needed to do the job,” says Jacob. “People in our industry care about getting the job done and less about the tools used.”

In an industry where success often is measured in time; minutes and seconds matter, so clarity of communication is critical.

“On any given project, people need specific data to get their part of the job done,” continues Jacob. “What works for one person might not be the best solution for another. Depending on the problem to be solved, 2D, 3D or both might be the right tool. As such, our tools should be tuned to provide the information and flexibility individuals and teams need to get their job done.”

The ability to seamlessly move information among the various available tools (e.g., hand sketches, 2D drawings, 3D models, animated renderings, simulations, etc.) is a primary unifying feature that will unlock the full collective potential. This is reminiscent of the conversations I had with industry professionals regarding digital twins, and many software and hardware developers are eager to oblige with products that facilitate the best of both worlds.

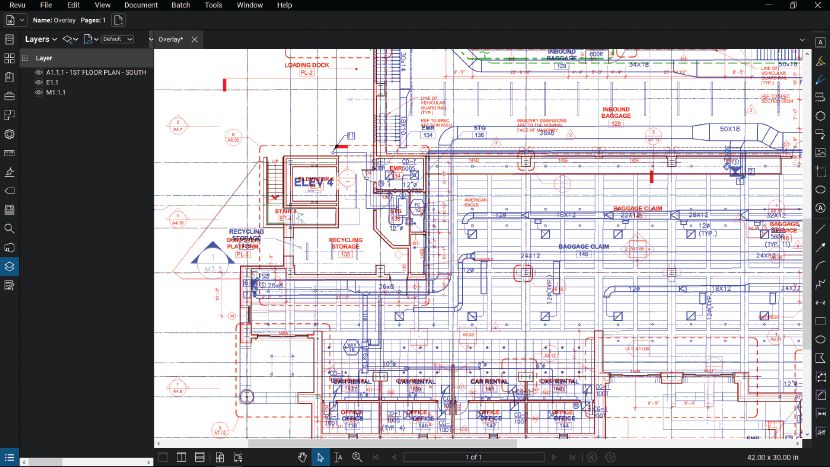

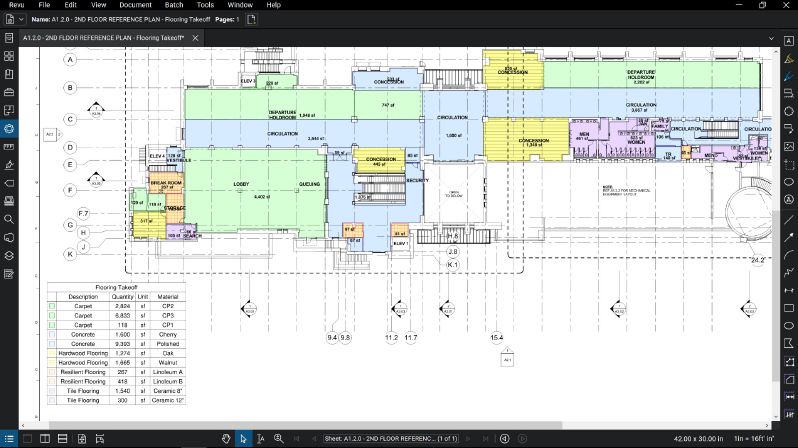

A PDF shows quantity take-off in Bluebeam Revu.

The Space Between: Bridging the Gap

According to Jacob, Bluebeam was created in 2002 to facilitate the move from hardcopy paper to digital paper (PDF)—to unlock the data in paper drawings and “supercharge” the paper view. As a tool, “Bluebeam helped standardize the communication among team members and record that ‘conversation’ in a familiar PDF file format,” says Jacob.

Similarly, today’s design and drafting tools and the ecosystem in which they exist can help ease the flow of information.

“AutoCAD and MicroStation now give us direct access to GIS data inside our CAD environment,” says Garrigues. “We can now easily import aerial images, point clouds, PDFs and CAD linework from other systems. This makes the design intent and data more transferable, more interoperable, and makes it easier to use downstream throughout the project and/or facility’s lifecycle.”

This interoperability, while not specifically related to 2D or 3D environments, eases the flow of data, making it easier for designers to not have to choose between the two.

Lefebvre with Vectorworks provides another example. “2D lets you get more artistic with the creation of the model,” he explains. “Via styles, annotations and the 2D graphic capabilities of Vectorworks, you have the tools to ‘beautify’ the 2D drawings output from a 3D model. Vectorworks includes the Renderworks feature set, an integration of Cinerender by Maxon. Renderworks allows several styles of rendering you can extract from the 3D model. From there you can add any 2D graphics similar to those in graphic editing tools like Adobe Photoshop, which is used to add color, transparency, depth, shadow, shading and more.”

Lefebvre goes on to explain that Vectorworks is a hybrid environment. Users can create 2D, 3D and visualization renderings. “Users can stay in 2D or 3D entirely,” he notes. “Hybrid gives them the best of both by allowing users to maintain the quality of the 2D output based on the 3D model. Geometry is created, and how you see it depends on the perspective.”

Similarly, Slater explains “Allplan’s 2D/3D hybrid approach links 2D linework to 3D models with attributes with information about what the line represents. The current workforce uses 2D, but they are expected to start transitioning to 3D. Allplan itself helps users learn 3D by easing the transition. And it works both ways: 2D and 3D objects are created simultaneously with a bi-directional link between them.”

More generally speaking, product developers have embraced open data standards that make it easier to design and draft, regardless of the dimension you’re working in. Vectorworks, Allplan and myriad other CAD creation tools can import and export a wide range of file formats, lowering barriers to the flow of data from 2D to 3D and integrating the products into the specific workflows of an organization.

“Nemetschek actively supports open standards like PDF and IFC,” says Jacob. “In some ways, IFC could be thought of as a 3D and data partner to PDF, in that both are great for information exchange and archiving.”

Taking a snapshot of a 3D model at a specific moment in time, especially those actively used on the jobsite, is more challenging than in 2D. “An open format like IFC might help address this challenge,” adds Jacob.

Communication/collaboration can be effective in a 2D PDF in Bluebeam Revu.

The Future of 2D CAD

The word processor hasn’t killed pen-and-paper writing, and the ebook hasn’t killed the printed book. Similarly, 3D modeling and simulation won’t kill 2D drawing and design.

However, the digital tools in these analogies have definitely reshaped our relationship with their predecessors: few people handwrite letters and instead opt for email. Yet it’s still commonplace to see handwritten meeting notes, journal entries and even your order at a restaurant. Similarly, while an entire industry has developed around ebooks and ereaders, publishers still are filling bookstores with printed books. At the same time, most printed newspapers and many magazines have floundered as readers now normally get their news online (this article is published in print and digitally, so we’ve got you covered!).

Sections were extracted from a 3D model and colored in Vectorworks.(Courtyard 33 | Design by 5468796 Architecture)

The near-unanimous consensus among those interviewed for this article is that 2D drafting, design and representation will be with us for quite a while, in a mostly peaceful coexistence with the growing trend toward 3D modeling and digital twinning.

“[2D] will be around for a while,” predicts Nemetschek’s Jacob. “It will continue to play a part in the ecosystem, coupled with 3D, and it is exciting to see approaches that blend and relate these ways of viewing projects. The industry needs to keep [2D tools] open, interoperable, accessible and used where they need to be used. Let’s not force 2D where it doesn’t belong, any more than forcing 3D where it doesn’t make sense.”

Vectorworks’ Lefebvre agrees, “I don’t think it’s going away anytime soon. It will stick around, fulfilling the same role as today, with a more-prominent role on the artistic side, supporting the 2D design process. Eventually, its use will fade as the industry adopts new and improved technology.”

New and improved hardware and software technology—such as AI-assisted design and drafting, and augmented reality—will facilitate the eventual melding of the simplicity and portability of 2D sketching and design with the power of full, data-rich parametric 3D models.

“Today, we have tools that will let us create almost anything, from football cleats to football stadiums,” says Garrigues. “Most of us need to create some very specific things, things we have been creating for a long time. I see the future of 2D and 3D CAD giving users the specific tools they need to create the specific things they need to create in the moment and context they need to create them.”

“3D will never be required in certain scenarios, and 2D will always play some role in others, although lessened significantly,” adds Cliggott.

So while 3D probably won’t kill 2D any time soon, it will shape and reshape our relationship with it as 2D evolves to occupy a new, more-useful place in our collaboration toolbox.

About Mark Scacco

Mark Scacco, P.E., is a 25-year veteran of AEC technology and design consulting. He is an AEC Industry Consultant with Scacco LLC and can be reached via email at [email protected].