Connected Traffic—Learning from Smartphones to Develop Smart Cities

Back in the waning years of the 19th century, two innovative inventions were beginning their revolutionary paths to change the world. Telephones were just becoming available, and they brought with them the promise of instant and direct voice communication. Meanwhile, growing urban density and horse-drawn traffic created the need for safety and standards to keep streets safe, and the traffic signal was born.

Despite not having much in common on the surface, telephony and traffic signals followed similar paths of development for the next 100-plus years or so. There were periods of heavy adoption and expansion marked by occasional bursts of innovation. For telephones, improvements included rotary phones, then push-button phones, and eventually cellular phones and smartphones. On the traffic-signal front, there was an evolution from human-powered signals to electric signals to traffic cabinets, remotely controlled lights and timed intersections. By the start of the 21st century, fiber-optic lines had become the backbone networks for telephony and transportation infrastructure, providing the foundation for more amazing innovation to come.

Both technologies continued to improve, until about a decade ago when telecommunications leaped forward and traffic-signal innovation stalled. When Apple launched the iPhone in 2007, it kicked off the modern era in which phones transformed into pocket supercomputers. There has been no comparable transformation for intersections.

Compared to other industries, transportation technology is like the car that stalls when the light turns green. Traffic is whizzing by on both sides, but we’re just sitting still, watching the future move forward without us. It’s not too late, however, and the transportation industry can learn a lot from how other technology companies changed the world.

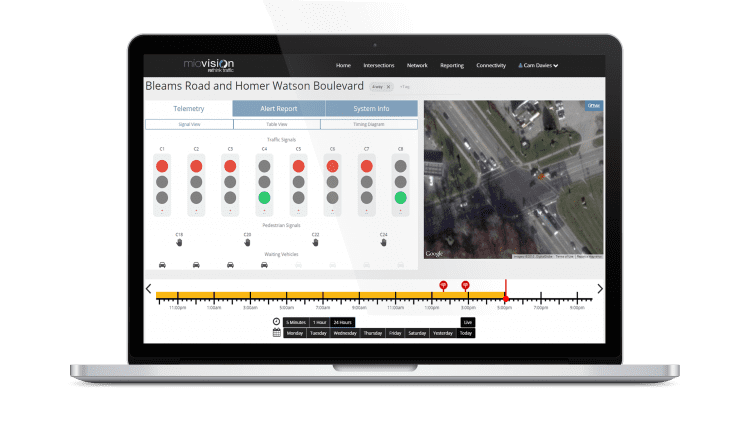

Managers can see live phasing, phase history reports, and error logs alongside video for additional context, enabling them to prioritize response times and use the right tools when a light goes down.

Hardware + Networks = Services

Before you start to think I’m suggesting that people will carry traffic signals around in their pockets, allow me to state the obvious: I am not saying that. But think about how the rise of the smartphone changed how people think about telephones. We call them “phones,” but that barely suffices.

Of all the hundreds of times I pull my smartphone out of my pocket in a day, I might use it as a phone once or twice. As amazing as the invention of voice mail was, some people now get angry if you leave them a voice message on their phones. Instead, my “phone” is for data. It’s my portal to a world of information and applications.

The most-innovative companies get this—think about the companies that repeatedly show up in technology headlines. Airbnb has become one of the largest lodging companies in the world, but it owns no real estate. Uber has emerged as one of the largest ride providers, but it owns no cars. Waze is a leading provider of real-time traffic data, but it owns zero road sensors.

These companies are disrupting industries that have been mostly stable for generations, because they understand there has been a fundamental shift in how customers derive value. The value is no longer in the physical asset; it’s in the data services and applications that the hardware enables. Telecom companies smartly recognized where the trend was going, and made it cheap and easy for customers to upgrade to more powerful handsets that could handle the applications and data.

Of course, hardware and applications don’t exist on their own. They require fast networks, and many transportation planners have wisely invested in building out their networks over the last several years.

Miovision’s Spectrum device plugs into existing traffic cabinets to connect traffic signals to the cloud for remote monitoring and management.

Changing the Status Quo

The status quo for most municipalities has been to upgrade older signal controllers, lay miles and miles of fiber, buy new servers, repair line-of-sight communications and upgrade congestion-management systems. Those approaches have their benefits.

On the positive side, the cities get to own the networks, keep the expertise inhouse and estimate total cost of ownership from the beginning. However, it’s extremely capital intensive, and the benefits won’t be realized for more than 10 years down the road. Plus, owning the network means maintaining the network and all the costs that come along with that, and the owners must have inhouse expertise, which means having engineers on staff and replacing them quickly if they leave. To continue the telecom comparison, it would be like everyone owning their own phone network. Sure, the calls would be free, but it would be inefficient and outrageously expensive to set up.

Traffic projects are long and complicated. The process was designed that way because it was created for major capital projects designed to last for generations, and it has been perpetuated by the large companies who build and install infrastructure. It’s a 1970s model that puts profits ahead of citizens, and it hasn’t evolved with the times. It’s a system that’s stalled at a green light.

Today there are alternatives to buying servers, tearing up streets to lay fiber and installing line-of-sight communications. We can get more out of the infrastructure that’s already in place and help cities, counties and states be more effective with taxpayer dollars. At the same time, we’d allow transportation officials to focus on what gets people from Point A to Point B the fastest, instead of dealing with IT.

Smart Cities Require Openness

This is where the lessons from the world of smartphones come into play. Developers need to shift their thinking about intelligent transportation systems away from adding more infrastructure to leveraging the infrastructure already in place and treating it like a platform for innovation. They need to think about traffic cabinets like they’re smartphones, becoming the platform to make “smart city” visions reality.

The genius of the iPhone wasn’t the handset itself; it was Apple’s decision to open up the API so third-party developers could build apps for it. You don’t have to buy a new phone every time you want a new app; you just install the app, a 30-second process. The same can be done with transportation systems without tearing up what’s already there to install new fiber-optic lines.

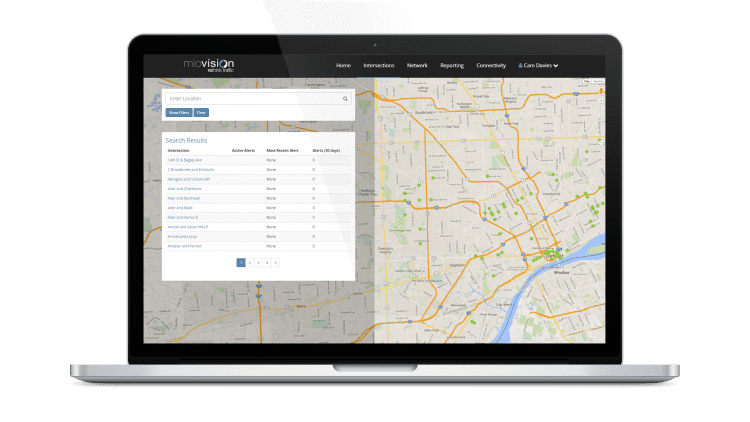

Instead, every intersection can be connected to the cloud, so traffic signals can communicate with each other and respond to traffic data from other sources in real time. If a sensor or camera detects an accident at one intersection, the smart signals could automatically adjust the timing of the lights at surrounding intersections to clear the logjam more quickly. In another scenario, a huge sporting event just ended, and thousands of cars are pouring out of the parking lot. Adjusting signal timing in the area should be an automatic solution that doesn’t require an engineer to push any buttons.

There are broader implications of a cloud-connected intelligent transportation network. Self-driving cars are drawing all sorts of buzz along with plenty of concerns about safety and security. Those autonomous vehicles will need to communicate with the infrastructure somehow, but how can they if the infrastructure is a closed loop?

There are countless possibilities for connected devices and transportation apps. Already apps such as Waze and Uber are changing the paradigm—there are now applications to help find available parking spots, for example. These emerging mobile solutions are just the tip of the iceberg, but there’s currently no path for them to connect to existing infrastructure. Our infrastructure needs to catch up.

To be clear, traffic signals aren’t the end game. Connecting signals for real-time traffic management is just one benefit drivers will get from a connected, open network. The signals simply provide the backbone for the network; they become the operating system for traffic management.

Just because a technology is part of critical transportation infrastructure doesn’t mean best practices developed in other parts of the tech world can’t be used. Without an open system, there’s no access to add anything. More openness means more collaboration, and more collaboration means more innovation. It’s past time to open up the system so responsible innovation can flourish.

Back when Alexander Graham Bell made that first phone call, he might have foreseen a worldwide network of phone lines, but he never could have envisioned how telephony evolved into smartphones and the services they enable. Similarly, the traffic cops who manually changed colors on early traffic signals never could’ve imagined a world where signals communicate with each other and automatically adjust to maximize traffic flow. Yet that’s the reality, and we’ve only scratched the surface. The light is green; the industry needs to turn the key and step on the gas pedal.