Don’t Believe in Magic: Berne, Switzerland, Demonstrates 20 Years of Public Works Coordination

Smart City, Building Information Modeling (BIM) and Asset Lifecycle Management are today’s buzzwords to put a magic spell on many an infrastructure manager. How nice would it be to control unwieldy roads, bridges and tunnels, distribution networks or even an entire city by myriad light pulses in a fiber optics fabric and wirelessly through the air? How beautifully safe and sustainable would our cities be if maintenance and restoration could be budgeted and scheduled according to continuous monitoring of usage and wear combined with lifespan prediction modeling?

However smart technological promises might be, we all have seen these dreams burst by organizational shortcomings, unreliable base data or the lack of sense for coordination and cooperation. With such experience, the 20-year history of public works coordination in the City of Berne, Switzerland, must remind us of a fairy tale of some enchanted town behind seven snowy Swiss mountains.

Gas Explosion Triggers Change

On Nov. 5, 1998, a gas explosion on the arterial road Nordring in Berne killed five people and destroyed a five-story building. The cause was a leak in an old gray cast pipe, a conduit type of which 34 kilometers still were in use at that time. This dangerous legacy had to be eradicated as quickly as possible, and the pipe replacement project touched nearly 10 percent of the road network.

Town engineer Hans-Peter Wyss formulated a vision to replace the gray cast pipes as well as renew the entire underground infrastructure in a coordinated way. But how could all information be collected to coordinate 33 utilities, the town planning office, emergency services and public transport operators?

Within three months from March to May 2000, GeoTask, a start-up company from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne and pioneer in OpenGIS standards implementation, developed a new type of internet application. It allowed people to submit construction and restoration projects as well as coordinate them geographically and through time. From June to August 2000, the 33 relevant actors proposed 2,000 projects. Such immediate adoption of a totally new technology for project submission can be explained by the “dot-com enthusiasm” of that time as well as because formerly difficult-to-obtain survey plans were easily accessible in the web application, many years before the appearance of Google or Bing maps and more than a decade before such services became publicly available in Switzerland.

During the last 18 years, the coordination application was continuously kept at the leading edge of Web- and process-centric geographic database technology. After a major service and security redesign, it now runs on the GeoTask System, a generic spatial asset lifecycle management engine. The optimal use of technology is one pillar of the unique open-minded cooperation culture in the City of Berne. The second, equally important pillar is the public works coordination process.

A screenshot shows the authorization management software interface.

Designed for Open Cooperation

Coordination in public space comprises five processes:

1. Submission of projects

2. Coordination

3. Request for comment

4. Authorization

5. Construction project supervision

It all starts with the needs and requirements of the agencies managing spatial assets or planning and designing public spaces. They communicate every future modification to the other agencies by drawing the perimeter of the project on the map and indicating project details such as the type of work to be realized, the preferred date of realization and the contact of the person responsible for the project. All other projects are visible in the same system. Not surprisingly, project managers often start informal coordination immediately with other agencies having a project in the same area.

The formal coordination process is led by the coordination unit of the department of public works. A coordination proposal is created by linking projects that are geographically co-located. By considering other projects in the neighborhood as well as traffic deviations scheduled on major axes, the department of public works tries to find the ideal timeframe for a coordinated project. The coordination proposal then is submitted to all agencies with a request for comment. In the same open spirit as for project submission, all agencies can see detailed digital plans of the projects involved as well as all comments of others. This avoids duplication of efforts and leads to a well-informed and engaged community.

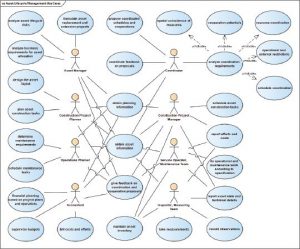

A chart shows possible use cases for coordinated asset lifecycle management.

After the closure of the request for comment, the public works department analyzes all the responses to eventually include further projects or modify the coordination proposal. At this moment, the process leaves the digital path. Classic project planning roundtables are organized to effectively shape the final coordinated project. The key parameters are fed back into the web-based coordination tool.

The authorization process ensures that no project slips in without being coordinated. For emergency measures, there’s a shortcut that at least informs all parties having projects in the vicinity. With authorization, the schedule of realization is fixed. This is particularly important for traffic management, because coordination comprises all measures for traffic deviation and imposes strict construction bans on alternative routes. The construction plan for the entire city is fixed in fall for the next year and adapted in case of emergency.

The authorization finally triggers the construction project supervision process by creating the required records in the database. From there, construction sites are automatically published on the public city map of Berne (https://bit.ly/2CLGd28). The supervision comprises all tasks in the public interest of having a state-of-the-art realization of the infrastructure as well as a flawless reconstitution of roads, greenspaces and public installations after completion of the work. All relevant stages and deficiencies are recorded to be able to track warranty and liability if needed.

Berne is the capital of Switzerland and features a medieval city center on the UNESCO World Heritage list with origins dating back to the 12th century.

Smart Processes Defeat Magic Promises

When asking Google how to “make your city smart,” you get more than 3 billion answers. Without claiming to have studied even a nano-fraction of this information wealth, a new Smart City 2.0 concept leaving the premature plug-and-play automation promises and moving toward ICT-supported coordination and cooperation processes can be spotted.

Already 20 years ago, the City of Berne, with visionary leadership, supported all players with a transparent process that made cooperation highly attractive. To use leading-edge technology was a risk, but there was no other way to provide real-time GIS interoperability among 33 organizations in the year 2000. The GeoTask technology evolved and is used today for complex tasks such as the planning and construction project management of the Swiss nationwide fiber optics network, the operation and maintenance of freeway infrastructures between major agglomerations and in the Swiss Alps, or the management and analysis of Liechtenstein’s public environmental data.

With a medieval city center that’s on the UNESCO World Heritage list, space for construction sites is scarce, and disruption of services must be kept to a minimum. The internet-based coordination process created a holistic view of all projects with their impact on traffic, inhabitants and local business that allowed the department of public works to gradually proceed to larger and more-complex projects.

For the total renovation of the central railway station square, traffic with usually 10,000 vehicles per day was totally shut down for 18 months to be able to efficiently construct all infrastructures of all utilities at once without compromise. Coordinated construction led to a systematic cost reduction of an average of 10 percent for all parties involved.

The success of public works coordination in Berne is grounded on the optimal blending of cooperative processes and supportive technology. The real magic, however, sparks from individuals and organizations willing to change their attitude toward cooperation and doing their job in a radically different way.