Future Forward: Use a PERMIT System to Promote Safety on the Job Site

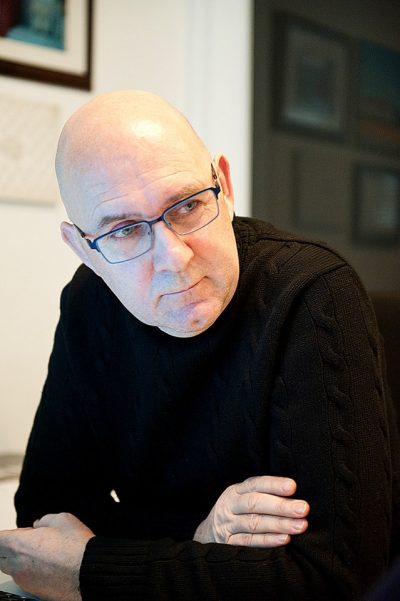

Patrick Tarrant is the founder and CEO of Crane Management, a consulting agency for construction companies in New York City. A well-known industry professional with more than 40 years of experience, Tarrant is frequently hired as an expert witness in construction and safety cases. Trained in all areas of crane operations, he is a certified hoist operator, master rigger, American Welding Society-certified welding inspector and Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA)-authorized safety instructor.

Organization

Crane Management oversees crane and rigging operations in New York City. As a master rigger and certified crane operator, Tarrant found a niche that needed to be filled when he started the company in 2015. Also, as an OSHA-authorized safety instructor, he’s on a mission to keep job sites safe for workers.

Unfortunately, construction accidents have increased in recent years, so Tarrant has his work cut out for him. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the leading causes of private-sector worker deaths (excluding highway collisions) in the construction industry were falls, followed by struck by object, electrocution, and caught in/between. These “Fatal Four” causes were responsible for more than half (64.2 percent) the construction worker deaths in 2015.

Tarrant attributes the rise in accidents to the booming construction industry. According to OSHA, the industry had 6.5 million employees working across hundreds of thousands of sites in 2016.

“There may not be more accidents on a percentage basis, but it pro-rates with the industry,” explains Tarrant. “We’re extremely busy now, and that creates some problems. Obviously the number of accidents will increase if the rate stays the same, but, more importantly, people are in a bigger hurry now. Developers want to get their buildings up and finished to catch the economic cycle.”

According to Tarrant, subcontracting also poses problems, with competing entities onsite that have to get out of each other’s way.

“One guy has to finish before another guy starts,” he says. “As a result, there’s a general sort of … I would call it a hysteria to get the job done at all costs and get out of the way to let the next trade in.”

Improving Site Safety

Tarrant believes most construction company executives understand they need to get the job done without accidents, but they also understand the cost of delays. The guys on the ground floor have OSHA training, so they know there are certain things they must do. But he often sees problems with field managers.

“There isn’t enough buy in from them,” claims Tarrant. “Although site-safety people are onsite, they often report to field managers, and field managers are getting pressure from executives to get the job done.”

To help improve site safety, Tarrant’s company promotes PERMIT, a system that provides a valuable checklist for any construction job, clarifies what’s needed to get a job done safely and forces buy in from field management. The “P” in PERMIT stands for personnel; subcontractors must have the personnel to do the job, and those people have to be trained properly. The “E” stands for equipment; workers need the proper equipment to perform the job and enough of it. “R” stands for “room to work”; there has to be enough space to work. According to Tarrant, a contractor will often shove the next trade in when the previous trade isn’t clear, and that creates a hazardous situation.

“Again, field management often responds to the push, push, push coming from upper management, and that can create an adversarial relationship between field managers and site-safety professionals,” relates Tarrant.

“M” stands for material, “I” is information, and “T” is time. These are the elements required to get a job done safely, but there has to be universal buy in. In Tarrant’s experience, too often each group has its own way of doing things, so workers are at the mercy of the lowest common denominator—the weak link in the chain.

“It doesn’t make much difference to me if I get hurt by my own crew or by somebody else’s crew,” says Tarrant. “I might be right, but I’m still injured or dead. This is where the field manager and the construction manager or the general contractor has to step up and say, ‘Listen, everybody is going to have to comply at the same level. Before you step on the job, I need to look at your PERMIT sheet. I want to make sure you’ve identified and secured the resources you need.’”

Steps to Success

Unfortunately, the PERMIT system isn’t universal. It’s more of an honor system, and workers often get to the job and don’t have exactly what they need.

“They have to improvise a little,” says Tarrant. “And I tell my guys, ‘Improvise is compromise.’ I will refuse to work if there are trades that are blatantly dangerous. I don’t care what the consequences are. I’m not going to have my men there, and I’m not going to go in there myself.”

So if Tarrant could sit down at a job site with every manager—the guys who tell their guys what to do—what would he stress to them?

“I’d tell them to institute a PERMIT system before any trade comes on the job,” he says. “And it’s important to implement the system across the board. … That would have a positive impact.”

Visit Informed Infrastructure online to read the full interview.

About Todd Danielson

Todd Danielson has been in trade technology media for more than 20 years, now the editorial director for V1 Media and all of its publications: Informed Infrastructure, Earth Imaging Journal, Sensors & Systems, Asian Surveying & Mapping, and the video news portal GeoSpatial Stream.