Montreal Adds Stunning New Bridges to Reimagined Historic Downtown

Ambient LED lighting creates a nice mix of night-time drama and secure intimacy.

In late 2022, the massive three-phase, approximately $131 million redevelopment of Montreal’s Sainte-Catherine Street West and Square Phillips was declared complete, ending a dramatic eight-year downtown transformation that began with the city’s simple, prudent desire to replace aging underground water infrastructure.

After that work was completed, rather than simply replacing the existing surfaces, the city took the opportunity to make big changes aboveground. To great acclaim—from local citizens and government officials as well as international urban planners and architects—spectacular improvements in livability, walkability, sustainability and, simply put, beauty were successfully achieved.

The Heart of Montreal

It’s all a little strange to outsiders hearing about Sainte-Catherine Street West for the first time. While the six blocks of street and its pleasing open space, Square Phillips, are deeply historical landmarks and universally loved by Montrealers, it’s interesting to note that the street was never part of any early city plan, and it’s not known when it was built—it just happened to be highly frequented. Nor can anyone say who exactly “Catherine” was—there are no less than three competing theories regarding the lady’s identity.

Minimalist planters and granite paving gradients frame and complement the decidedly maximalist 1941 Edward VII monument.

But starting in 1736 (aging infrastructure indeed), the street became intensely developed and is now an integral part of the downtown core as envisioned in the “1841 Phillips Plan” as well as the site of multiple interconnected large office-tower basements and shopping complexes; educational institutions such as Concordia University, McGill University, Université du Québec à Montréal, Dawson College and LaSalle College; nine metro stations; Place des Arts, the city’s primary concert venue; and Montreal’s Gay Village, which is closed to traffic entirely from mid-May to mid-September, becoming something of an open-air fair and market.

The Rebuild

Multi-disciplinary architectural firm Provencher Roy, founded in 1983 and headquartered just a few blocks away from Square Phillips, was the lead designer and coordinator of all aspects of the aboveground redevelopment. As 40-year contributors to Montreal’s built environment and urban spaces, the firm seems “destined by Sainte-Catherine” to be involved here, but were they eager to be the face of such a huge and potentially controversial transformation of a much-loved city center?

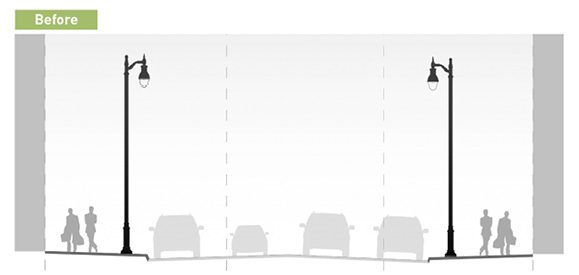

The transformation of Sainte-Catherine Street West was conceptually simple: reduce the number of lanes, widen sidewalks drastically, and add bicycle lanes and trees.

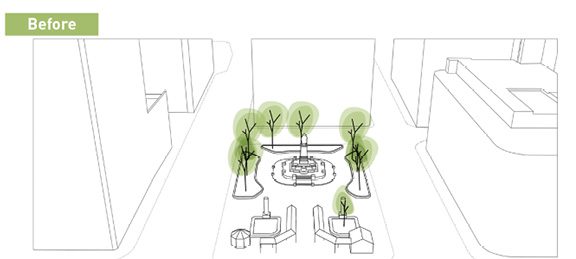

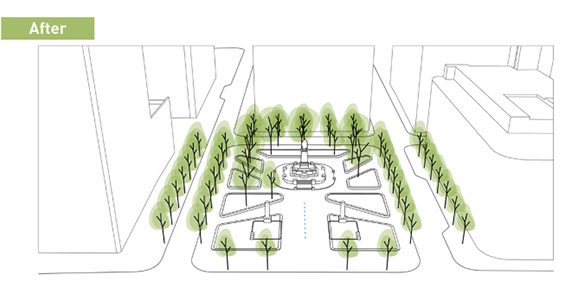

Existing trees and plantings at Square Phillips were increased 14-fold, pedestrian space was expended, and built infrastructure was eliminated and/or streamlined.

“Yes!” says Architect Partner Sonia Gagné. “We are pleased to have made a significant contribution to this important urban revitalization project for Sainte-Catherine Street West—to enhance the business artery’s reputation in the retail realm, not to mention its nationwide visibility. Equally, the redesign drastically increases the greenery in this area, enhancing the pedestrian experience and making for a more-sustainable urban realm. The project increases vegetation by 46 percent, and we’ve planted 14 times the original number of trees.”

In addition to the infrastructure work, the project, stretching from De Bleury to Mansfield streets, included widening the sidewalks and reducing the number of traffic lanes to one; significant greening; and the addition of street furniture, smart and energy-efficient LED lighting, charging bollards for electric vehicles and complimentary WiFi.

The stunning redesign of Square Phillips (built in 1842) is fast-gaining iconic status as an internationally recognized Montreal landmark. Some numbers and new features include the following:

• Pedestrian area more than 35 percent larger

• A fountain lawn with seven water jets

• Granite paving stones

• Two restored monuments (Edward VII and Blue Bird)

• Doubled greenspace area

• Distinctive street furniture

• 75 percent more seating space

• New LED ambient lighting

• Free WiFi network

• New, more-reliable underground infrastructure. Before the Square was redeveloped, the public toilets dating back to 1931 were removed and the soil decontaminated. The outdated sewer, water, electrical and gas networks on Avenue Union were replaced. The gas networks also were repaired on Rue Place Phillips and Rue Cathcart around the square.

From (Below) Ground Up

In addition to the replacement of sewers and water pipes, subsurface work also included reconfiguration of drainage systems to account for greatly increased surface permeability due to increased greenery. “The increased amount of vegetation has significantly contributed to surface permeability, allowing for stormwater to get absorbed and be collected within the site’s green areas,” says Gagné. “Surplus water is now expelled via a channeled drainage network.”

Sleek and subtle urban furniture lining Sainte-Catherine Street West and Square Phillips by famed Montreal industrial designer Michel Dallaire.

Greatly expanded pedestrian space creates a six-block promenade with a balanced “rhythm of intensity.”

There was a significant amount of contaminated soil to contend with—3,000 tons of it. Per geotechnical drilling studies, survey reports and chemical soil analyses conducted by project engineer CIMA+ and subcontractors, “the extent of soil contamination within a zone of level B-C and C environmental quality was 3,000 metric tons.” Mitigation was thorough from end-to-end.

According to Gagné, contamination was mitigated through development of a soil-management plan (establishing contamination polygons). The contractor had to comply with Ville de Montréal’s “Devis technique normalisé et spécial – Gestion des matériaux excavés” [standard and special technical specifications, management of excavated materials] and any additional regulations in place. The mitigation strategy included selective soil excavation and transportation of contaminated soil offsite to a location authorized by the Ministère de l’Environnement, de la Lutte contre les changements climatiques, de la Faune et des Parcs (MELCC).

“When choosing an external site to dispose of contaminated soil and other excavation materials, the contractor favored treatment and reuse of soil and materials, rather than landfill site options,” she notes. “Furthermore, the contractor was obligated to keep precise updated records of all materials eliminated from the construction site. Among additional information, these records consisted of weigh bill numbers for contaminated soil eliminated offsite, locations of soil disposal, quantities of soil disposal (in metric tonnes), and the date of disposal.”

Street design and movement flow were part of Provencher Roy’s landscape design scope. Working with project engineers CIMA+, they transformed a four-lane road into a pedestrian-oriented street with a single lane of car traffic, creating a promenade stretching six blocks between Bleury and Mansfield Street in which cars, cyclists and pedestrians share the street.

Conceptually, Provencher Roy’s plan for improving the “walkability” of Sainte-Catherine Street West and Square Phillips was simple: eliminate street parking, widen sidewalks “drastically” and remove lanes.

“Flipping the proportion of space allocated to cars and pedestrians turned it into a place for people,” says Gagné. “The new shared street creates a linear plaza that links the previously disjointed network of squares, monuments and historic buildings into a cohesive urban landscape.”

The simple concept required a nuanced approach and close attention to detail to create a pleasant plaza for strolling and refreshment, and not just “more room to walk.” Bronze plates set in the street serve as urban markers, identifying the grand turn-of-the-century department stores and commercial buildings that lend the street its storied heritage. Newly laid modular paving marks different spaces and their uses. A gradient from dark gray to light gray unobtrusively informs users on limits of vehicular lanes as well as pedestrian and bicycle zones.

Increasing greenery was more sophisticated than simply planting more trees; trees were grouped closely in areas intended to be quieter and spaced out in livelier zones to create a balanced “rhythm of intensity” across a single, unified “green heart for the city.”

Minimalist, Maximalist? Who Can Say?

The impression formed when first viewing the reimagined and rebuilt Square Phillips is that Provencher Roy designers created a minimalist masterpiece of urban open space with clean lines and sleek detailing that smooths out long views and in which the pedestrian conventions of a downtown central square merge seamlessly with traffic and commercial activity.

But look more closely, and one wonders if “minimalist” is quite right. A lot is going on in the Square Phillips redevelopment, and the focal point since 1941 continues to be the richly meaningful Edward VII monument:

Four allegorical figures sit at the base of the monument: Peace is the woman at front, holding an olive branch but keeping a sword hidden in the folds of her skirt. The western group is Four Nations, representing Montreal’s four founding nationalities—French, Scots, Irish and English—living together in harmony. At the back of the monument, Winged Genius represents liberty; the angel has broken the shackles of religious prejudice and persecution and is intended as a reminder of the King’s extended respect and dignity to all his subjects, regardless of race, color or creed. Abundance is on the eastern face, representing Canada’s material prosperity.

A simple, seven-jet fountain lawn that’s ‘just enough.”

So, a “maximalist” public installation if ever there was one and, don’t forget, the planting of the square was greatly expanded. Gagné says, “Existing shade trees are preserved, and new ones have been added to frame the street. Reminiscent of the Victorian garden history of the site, lush flowerbeds are juxtaposed with more-robust plantings conveying soft hues in violet, blue, pink and white. The square therefore becomes an oasis of greenery in the city defined by its rough-hewn naturalistic aesthetic echoing English garden design.”

And yet, no one will ever accuse Square Phillips of being too busy or crowded with superfluous construction—the impression persists of clean open space in the midst of a bustling retail and commercial zone. Provencher Roy designers achieved this peaceful balance of lush and sparse with subtlety in the benches and furniture (created by famed Québécois industrial designer Michel Dallaire), in the soft-gray gradient pavement delineating pedestrian zones, a fountain lawn with seven simple jets that is “just enough” (by Montreal fountain engineer François Ménard), ambient lighting with no hint of glare and a thousand more details that will never be known by anyone but designers and builders. And no-one complained about the complimentary WiFi.

All in all, the reimagining of Sainte-Catherine Street West and Square Phillips—in the midst of the busiest zone in what might be North America’s most beautiful city—appears to be a universally popular and unqualified success on all levels, from desperately needed subsurface infrastructure rehabilitation to street-level reallocation of vehicle and pedestrian space to the top of a massive monument and the airy canopies of hundreds of new shade trees. And, given the close involvement of Provencher Roy and many more local designers, artisans and builders, it also seems to be a reimagining “by Montrealers for Montrealers.”

Provencher Roy Valorizes Montreal’s Roadway Infrastructure

In the last several years, Provencher Roy realized or renovated several spectacular Montreal landmarks in addition to the reimagining of Sainte-Catherine Street West and Square Phillips, including the Archeology and History Complex, the Museum of Fine Arts, the Museum of Contemporary Art, La Maison Théâtre, and multiple downtown commercial or residential buildings.

At the same time, Provencher Roy makes room in its practice for more-humble civic projects, including the reconstruction of the Darwin Bridges on Nuns’ Island (in the middle of Montreal in the Saint Lawrence River). It’s not often that a pair of two-lane bridges and a pedestrian and cycling underpass receive the concentrated attention of a world-class design firm, but such is the case here: the elegant, understated form of the new bridges as well as the novel and efficient material choices elevate what could have been utilitarian urban infrastructure to something like a destination in itself—a new island landmark. This is partly out of respect for the original structures.

“In the 1960s, urbanization of the island was originally inspired by the new residential suburbs cropping up in the United States,” explains Project Manager Jacques Rousseau. “This included numerous pedestrian pathways, as here, separated from roads and connecting residential zones to community parks, like Parc de West-Vancouver.” In addition, Provencher Roy saw an opportunity to innovate and make major contributions to Montreal’s sustainability and local economy.

Excavation and stepped retaining walls create a lush “secret garden” for the enjoyment of bicyclists and pedestrians (top). The reconstructed Darwin Bridges strongly emphasize the existing curves of Boulevard De l’Île-des-Soeurs, winning over Montreal planners (middle). Abstracted floral detailing and minimalist-but-warm lighting create a sense of “placeness” in the underpasses (bottom). But one worries about the lamp stands and cycling accidents.

Replacing 1960s Avant Garde with 21st Century Avant Garde

Rousseau admires the design intent of the 1960s bridges but acknowledges that an update was needed. “The concept was always there, but the design and construction standards of the time favored the automobile, with corrugated galvanized iron guardrails to prevent vehicles from falling,” he explains. “We were working in a paradoxical 1960s context, on an innovative urban project to improve the user experience, while also contending with the formal regulations required for road transportation. We attempted to reconcile these two constraints with a solution that enhances the architectural language and fulfills safety regulations.”

To pull off this balancing act, Provencher Roy based its bridge design on swooping, curved formwork (a design that won over Montreal planners); eliminated galvanized iron guardrails; integrated a security buffer of more than

4 meters; and followed the curvature of the roadway to create elegant 37-meter twinned spans.

Reconstruction of the underpass also was a design priority. Starting from the highway, two circular arches descend the slope toward the cycling path, delineating the pedestrian crossing enclave; the central median strip between the two bridges was opened up and dug out; and stepped retaining walls were built to create a terraced and lushly planted “secret garden” visible only to those on foot or bike.

Subtle finishing touches are provided by abstracted floral detailing, while at nightfall the pathway is illuminated with warm LED tones. All of this makes the sunken space airy and mitigates possible feelings of confinement or insecurity.

Impressive, right? But wait until you hear about the cutting-edge concrete that was used.

Sustainable, Beautiful Ground Glass Pozzolan

“The structural concrete formula was developed by the City of Montreal and uses 10 percent finely ground recycled glass as a ternary binder,” says Provencher Roy Architect and Sustainability Expert Céline C. Mertenat. “Ground glass pozzolan (GGP) has been used previously in street furniture and non-structural elements such as curbs and slabs, but we’re pretty sure this project marks the first use of GGP for all of a bridge, including structural components.”

The city worked with the ‘Société des alcools du Québec’ (basically, Canada’s liquor board) to develop this particular GGP recipe intended to use the many tons of mixed glass from wine and spirits bottles collected at recycling centers. Approximately 40,000 kilograms of such glass—representing 70,000 wine bottles—were used, reducing greenhouse-gas emissions by 40 tons while also contributing to the local economy and reducing transport emissions because the material is made in Montreal.

“And it should last a while,” adds Mertenat. “Preliminary studies show that it’s more impermeable and resistant, and we used stainless-steel reinforcement to nearly double the expected bridge lifespan to 125 years.”

And beyond those practical benefits, the GGP that comprises the new Darwin Bridges is strikingly beautiful. “The finished concrete is noticeably whiter and lighter, and even sparkles a little,” explains Mertenat. “It holds the finely molded floral details crisply, and it complements all the desired curves and shapes in the formwork. We’re very pleased with this material choice.”

Basic roadway infrastructure designed to a high standard and crafted of exquisite materials with sustainability gains? More of this please.

About Angus Stocking

Angus Stocking is a former licensed land surveyor who has been writing about infrastructure since 2002 and is the producer and host of “Everything is Somewhere,” a podcast covering geospatial topics. Articles have appeared in most major industry trade journals, including CE News, The American Surveyor, Public Works, Roads & Bridges, US Water News, and several dozen more.