Needing Every Last Drop: Western States Are Recycling Wastewater in a Variety of Ways

A rendering shows the interior view of the membrane treatment area at the Advanced Water Purification Facility being developed in El Paso, Texas.

As water scarcity continues to be a concern—particularly in the western United States and as growing populations place more demand on water-delivery systems—communities are engineering ways to mitigate the challenge through recycled water projects.

Texas-Sized Water Recycling

In El Paso, Texas, El Paso Water (EPWater) is designing the Advanced Water Purification Facility, which will produce up to 10 million gallons of water daily to supplement the city’s drinking-water supplies. The focus is on purified water, because it’s a high-quality drinking water produced using the most advanced treatment processes available. While treated water from the city’s wastewater facilities is reused for irrigation and industrial processes, current technological advancements enable the city to take the next step with wastewater to create a drought-proof, sustainable resource, notes Christina Montoya-Halter, El Paso’s communications and marketing manager.

“Water passes through several phases of membrane filtration and disinfection using advanced water purification to transform the treated wastewater into a safe, reliable drinking-water supply,” she adds.

EPWater meets the challenge of serving a Chihuahuan Desert city by conserving water resources and diversifying the water supply.

“We balance water from the river and two underground aquifers and recycle treated water from our wastewater plants,” says Montoya-Halter. “However, upstream climate conditions can reduce river-water supplies, and El Paso’s population continues to grow. We need additional water resources to meet our customers’ demands.”

The project allows EPWater to continue conserving the Hueco Bolson aquifer, while adding an additional water source to meet the city’s demand during times of drought and fulfill long-term water-supply needs due to city growth.

In early 2016, EPWater completed a pilot test using a facility co-located at the Roberto Bustamante Wastewater Treatment Plant designed to purify cleaned wastewater through membrane technology, reverse osmosis, ultraviolet disinfection with advanced oxidation and granular activated carbon filtration.

Renderings illustrate various views of the Advanced Water Purification Facility scheduled to begin construction in 2024, including the front entrance (top), residuals basin (middle) and the groundwater treatment system (bottom).

Thousands of water samples were analyzed at state-certified laboratories, and results showed the purified water performs better than all primary and secondary drinking-water standards. The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality reviewed the pilot facility data and gave EPWater approval to proceed with design of the Advanced Water Purification Facility.

The project received $20 million in funding from the Department of Interior’s Bureau of Reclamation through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. EPWater is seeking additional funding, with the remainder to be funded by EPWater ratepayers.

The project is in the final plan review and regulatory approval stage, with construction slated to begin in 2024.

Idaho District Uses a Canal to Store Recycled Water

Idaho is one of the fastest-growing states in the country. Water needs could double in the next several decades as new residents and industries move into Canyon County. Water quality was an initial driving factor for the city of Nampa, Idaho, to establish a recycled water program designed to increase the water quality and direct 11 million gallons a day toward the Pioneer Irrigation District.

The recycled water system will operate under Idaho Department of Environmental Quality reuse permit that outlines monitoring and regulatory requirements to ensure optimal safety for the city of Nampa. Water will run through preliminary treatment, primary treatment, secondary treatment, filtration, disinfection and then to the Phyllis Canal.

The fully treated Class A water is monitored daily and continuously to ensure it meets standards and is safe for irrigation use in parks, playgrounds and schoolyards, golf courses, food crops, and residential landscapes. Additional uses include highway medians, roadside vegetation irrigation on both sides, cemetery irrigation, and orchards and vineyard irrigation during the fruiting season.

“We have a compliance schedule to be done with temperature by 2031 and then the phosphorus by 2026,” says Tom Points, P.E., Nampa’s senior director of public works. “We are looking to meet those limits by 2025.”

Points says temperature mitigation isn’t needed as it will match the canal’s water temperature. Phosphorus content also will match what’s in the canal, which then can be applied on lawns and farms downstream as it’s beneficial for plant growth.

“As we were building this program and had a drought, we realized this also is a drought-resiliency project,” adds Points. “The water we produce over the irrigation season is 15 percent of the total demand from our irrigation system during the season, and 5,000 acre-feet of water get fully consumed by six pump stations downstream of our discharge point in the canal.

“All the water gets used and put into our pressurized irrigation system before it leaves Nampa,” he says. “This allows the storage of water in the reservoir to be maintained there and extend out the season for the whole valley.”

The $250 million project has been financed in part by a $3 million federal WaterSMART grant used to build a pipeline for recycled water from the plant to the canal. Another $3 million was obtained by the Idaho Department of Water Resources to help with pipeline costs.

“Whenever a building permit is pulled, we have fees that we generate,” explains Points of wastewater impact fees. “Within our rates and hookup fees are another piece of how we’re paying for it.”

An aerial image shows construction at the Nampa wastewater plant as of September 2023. (City of Nampa)

A rendering shows what the recycling plant will look like in 2024. (City of Nampa)

Additional monies are derived from Clean Water State Revolving Fund loans that provided the difference.

“We spent almost 10 years just planning and figuring out how to fund it,” says Points of the challenges. “We’re excited we’re at the construction phase now, because that’s the fun part.”

Planning involved various outreach groups, including a large wastewater advisory committee that helped guide the decision and was compromised of citizens, business owners, realtors, elected officials and school representatives.

“We wanted to make sure the industries were involved because Nampa has a lot of industry,” says Points. “We have one customer that sends us 1 million gallons a day of water. [We consulted with] anybody we could think of that was a user and has an interest in it, because these groups end up paying for the rates for this plan.”

Whether stakeholders even wanted to recycle water was questioned and, if so, where should it be directed.

“Recycled water was not the cheapest option, but that’s what the community wanted,” he adds. “They thought it was the right thing to do.”

Another challenge was getting through all the steps necessary to get the permit.

“We were the first in Idaho to do a project this size with 100 percent of it going into a canal,” says Points. “Whenever you’re the first doing something, there are always hurdles. With the permit itself, there was a lot of discussion about the Waters of the United States. It was not connected to the waters of the United States. We have data and research to prove that.”

Points says the plant is being constructed to serve the community through 2040. The population currently is near 110,000, but Nampa has seen double-digit percentage growth the last few years. The water project also is expected to help with needed surface-water conservation.

In addition to getting stakeholder feedback, Points also recommends municipalities considering similar efforts to start projects early.

“Prices are not going down,” he says. “Inflation has gone crazy. The faster you can get one of these done, the better.”

Nampa was the first municipality in Idaho to do a progressive design build.

“That was really positive for us,” explains Points. “It allowed us to build the plant, build the new construction, keep the current operations going and then tie in the new facility that we’re building.

“It’s design-build, but a little bit different,” he notes. “There’s a guaranteed maximum price we sign up for. We save a lot of money there.”

This delivery format means there are no change orders because of the design, and the builder owns all the changes. In addition, there are acceptance criteria that the piping, plants and pumps have to work, and the treated water must meet the criteria of water-quality standards.

According to Points, Nampa is the first city in Idaho to do 100-percent water recycling and put it in a canal, something he says is unique in the Northwest, because not all regulatory agencies permit it.

“If more [communities] are recycling water, it gives us better options for water quality and conservation,” he adds.

The Harvest Water project will increase the amount of water available for agriculture while replenishing dwindling groundwater supplies. (Regional San)

A Water Harvest in California

The Sacramento Area Sewer District and Sacramento Regional County Sanitation District in California embarked on what will be the state’s largest “recycled water to agricultural irrigation system.”

Funding for Harvest Water has been provided in part from the Water Quality, Supply and Infrastructure Improvement Act of 2014 and through an agreement with the California Water Commission. In June 2023, the California Water Commission awarded Harvest Water $291.8 million in Proposition 1 grant funding from the Water Storage Investment Program.

The California Natural Resources Agency, California Water Commission, California Department of Fish and Wildlife, California State Water Resources Control Board, and the Harvest Water team collaborated to meet the project’s grant requirements.

In addition, Regional San has been conditionally awarded a $30 million grant from the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation as part of the Title XVI Water Reclamation and Reuse Program. Regional San serves a population of about 1.6 million in the area, providing wastewater conveyance and treatment services to residential, industrial and commercial customers throughout unincorporated Sacramento County; the cities of Citrus Heights, Elk Grove, Folsom, Rancho Cordova, Sacramento and West Sacramento; and the communities of Courtland, Locke and Walnut Grove, with new developments increasing the population.

Numerous private and public water suppliers in the Sacramento region collectively supply a mix of groundwater and surface water, the latter coming from the American and Sacramento rivers.

“The Resource Recovery Facility currently uses recycled water for irrigation and industrial uses,” says Mike Crooks, deputy director of Regional San operations. “It also delivers recycled water to the Laguna West area of Elk Grove for park and greenbelt irrigation, and to the Campbell Cogeneration power facility in Sacramento for use in their cooling towers.”

In 2007, Regional San sought to increase recycled water deliveries up to 40 million gallons per day and embarked on a water-recycling opportunities study, which identified delivering recycled water to agricultural lands in southern Sacramento County as a viable alternative to achieve those earlier goals.

Regional San initiated the planning effort for what’s now known as Harvest Water. At that time, the EchoWater Facility provided only secondary wastewater treatment except for a small filtration system that provided tertiary-treated water to Laguna West and the Campbell Cogen facility, Crooks notes. The ability to use secondary-treated recycled water for agricultural irrigation is limited to non-food crops.

In 2010, Regional San received a new discharge permit for its treated wastewater that required significant improvements to its processes, including the provision of filtration for all dry-weather discharges to the Sacramento River. This $1.7 billion upgrade to the treatment processes—the EchoWater Project—was completed in 2023. Treated water now produced by the EchoWater facility meets water-quality standards for unrestricted recycled uses. Regional San treats an average of 135 million gallons of wastewater per day.

When complete, Harvest Water will supply roughly 16 billion gallons of drought-resistant recycled water each year for local farmers to use for crop irrigation—instead of pumping out groundwater.

The project is set to boost sustainable agriculture by delivering up to 50,000 acre-feet per year of tertiary-treated recycled water to approximately 16,000 acres of farm and habitat lands in southern Sacramento County.

The Harvest Water conveyance system will be constructed through six different projects featuring a new pump station, a series of pipelines totaling more than 41 miles, and approximately 140 service connections to ultimately deliver water to the agricultural customers. Construction was set to start in 2023 and continue into 2026.

Extensive stakeholder engagement was critical to gain the support of environmental groups, regulatory agencies and elected officials, says Crooks. Securing grant funding also was critical to make the project cost-effective.

Challenges included getting the growers engaged in using the water to irrigate their crops; available funding vs. record inflation and construction-cost escalation; and the onset of COVID-19 just as the program entered the permitting and design phases.

By reducing the need to pump groundwater, Harvest Water has the potential to increase groundwater elevation up to 35 feet in about 15 years and, in the long-term, increase groundwater storage by 370,000 acre-feet, approximately one-third the size of Folsom Lake.

“The project will also sustain a healthy water supply for more than 5,000 acres of riparian and wetland habitats, support a longer migration window for fall-run Chinook salmon through increased streamflow volume in the Cosumnes River, and improve regional water quality by reducing the salinity load to the Sacramento River and Delta waterways,” adds Crooks.

His advice to others looking to start a similar project: “It’s key to identify and garner support from affected governmental agencies, regulators, other jurisdictions and stakeholders; and to engage them early in the planning process. Also look for low-cost or no-cost funding opportunities.”

Recycling more water in the Sacramento area will allow for more agricultural production (top) as well as creating a healthy water supply for wetland and riparian habitats such as for the Sandhill cranes (bottom). (Regional San)

Purple Pipe in Washington

For Cheney, Wash., mitigating water challenges has included a “purple pipe” (often used to differentiate water intended for non-potable uses) project to provide Class A reclaimed water from the city’s Wastewater Treatment and Reclamation Plant (WTRP). The project entails upgrades to wastewater effluent through ultraviolet disinfection and filtration processes; reuse water storage; a new pumping facility; and transmission mains to city parks and playfields as well as the Cheney School District playfields. The estimated reuse water production is 1 million gallons per day. Approximately 2.25 miles of purple pipe distribution main will be constructed to serve irrigation sites.

The project is estimated to cost $24 million, notes Todd Ableman, Cheney’s public works director, which would come from Washington State Department of Commerce and U.S. Bureau of Reclamation grants as well as a Washington State Department of Ecology loan.

With an anticipated completion date of 2026, the construction timeline starts with electrical upgrades at the treatment plant, followed by a reclaimed water-treatment system, reclaimed water storage and pump station, and a reclaimed water-distribution center.

Cheney currently obtains its drinking water solely from a series of eight groundwater wells, and water-level data have shown for years that groundwater mining is occurring within the underlying aquifer due to pumping from city wells. The city estimated that groundwater levels had decreased 20 feet within the previous 20 years and were expected to decrease an additional 11 feet within the next 20 years.

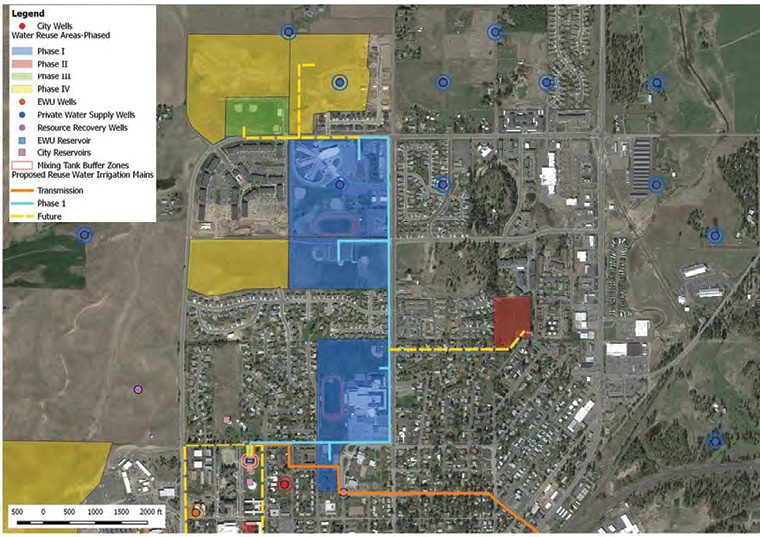

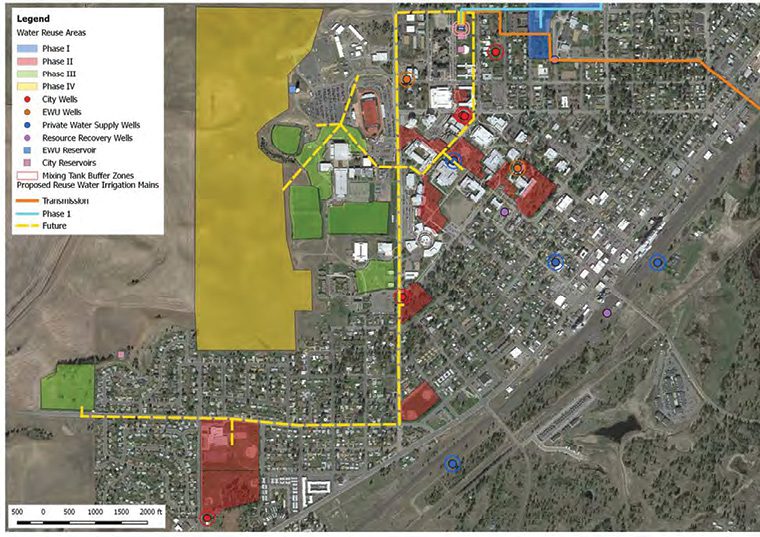

Figures show proposed reuse and recorded well locations on the north (top) and south (bottom) of Cheney, Wash.

“The reduction of using potable water for irrigation purposes will slow the drawdown of the city’s groundwater,” says Ableman, adding it also will eliminate watering restrictions associated with seasonal water-source deficit. Meanwhile, Cheney’s population is 12,300 and increasing.

An engineering study prepared by Esvelt Environmental Engineering in Spokane, Wash., estimates that offsetting the city’s well-water use by 1.0 million gallons per day of reclaimed water for irrigation from June through September will reduce the expected aquifer decline from 11 feet to 7 feet by 2026.

Cheney’s water-reuse project has been discussed since the Wastewater Treatment and Reclamation Plant began operation in 1994. According to Ableman, most of the time invested in the project has been spent applying for grants, loans or requesting monies from state and federal legislators. “Nothing gets off the ground without funding,” he adds.

About Carol Brzozowski

Carol Brzozowski is a freelance journalist specializing in technology, resource management and construction topics; email: [email protected].