Executive Corner: When Those Aging Baby Boomers Just Won’t Retire

Alan co-founded a successful consulting engineering firm when he was in his thirties. Through the years, the practice grew steadily, adding new staff, offices and owners along the way. When Alan turned 60, he announced his intent to retire at age 65. That was 10 years ago. Now, at age 70, he still enjoys his work, and while he’s cut back on hours, business travel and administrative duties, he still manages a significant portfolio of business. The last time someone asked when he planned to retire, he answered (tongue firmly planted in cheek): “the day after I die at my desk.”

Of course, Alan is a fictional character, but I would wager that many Informed Infrastructure readers have one or more “Alans” in their firms and may be wrestling with the challenge of how to accommodate such seasoned professionals who are able and willing to continue in full-time employment, while maintaining upward mobility for more junior staff.

Demographic Trends

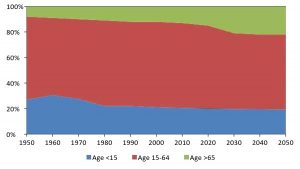

The aging of the working population during the last decade is an interesting worldwide demographic trend. According to the Pew Research Center, the population of people age 65 and older has been increasing in numbers and as a percentage of the total population since 1950, and this trend is projected to continue through 2050. Furthermore, the rate of participation in the workforce of those who are age 65 and older has been on the rise since 2007.

U.S. Population by Age Range (Historical and Projected)

When you combine the aging workforce trend with the emergence of the Millennial generation, which is projected to dominate the workforce for the next 30 years, you get some painful pressure points, including the following:

1. Upward mobility traffic jams. Boomers who postpone retirement and are unwilling to hand over the reins of management can create real tension in an organization—potentially driving off the top talent below them. The best leaders recognize when it’s time to step back from their senior management roles to create that opportunity for advancement. And the “best of the best” will do so early enough that their successors have a sufficient term to achieve their own vision for the firm.

2. The inability to accurately budget for stock redemption obligations. If “Alan” can’t tell us when he plans to retire, how are we supposed to budget for his stock redemption? That type of financial uncertainty will drive a CFO crazy. The problem can be particularly acute if Alan still is a significant or majority shareholder. In response, we’re seeing more firms incorporate mandatory divestment clauses into their governing shareholder agreements. In this way, a valued principal such as Alan can continue to be employed, even as his shares are repurchased.

3. The inability to adequately compensate (and thereby retain) top talent. There’s no doubt that this is the most-competitive marketplace for talent that the A/E industry has witnessed since before the 2008 recession. The best employees expect to be compensated appropriately, and the younger generations have shown themselves to be less patient than earlier generations and less inclined to “put in their time” or “pay their dues.” Ownership remains one of the most-effective ways to retain key staff and provide them with the opportunity to build real wealth for themselves through stock appreciation and profit distributions. But this requires older shareholders willing to part with their stock at a fair price.

Dealing with these challenges often comes down to price. Companies that price their stock too conservatively often create a situation where shareholders nearing retirement can’t be compelled to sell, because the profit distributions are too great, relative to the share price, to give up. However, companies that price their stock too high will find it difficult to convince new owners to invest.

The Opportunity

Ultimately, the challenge of the aging Baby Boomers (and the up-and-coming Millennials) may represent an opportunity for firms to rethink roles and responsibilities as well as how ownership relates to both. Stock divestment doesn’t have to mean retirement, nor does relinquishing leadership roles, although both are necessary to ensure the company’s longevity. At the same time, finding new roles for Boomers who aren’t ready to retire can be the key to preserving and transferring the wealth of technical knowledge and experience they represent.

About Ian Rusk

Ian Rusk, Managing Principal of Rusk O’Brien Gido + Partners, has spent the last 20 years working with hundreds of architecture, engineering and environmental-consulting firms large and small throughout the United States and abroad, with a focus on ownership planning, business valuation, ESOP advisory services, mergers and acquisitions, and strategic planning.