Drones Becoming Integral for Infrastructure Projects

Trevor Byrd, LSIT, Anderson Engineering survey party chief, uses a drone to inspect a bridge over the Spring River in Carthage, Mo. (American Public Works Association)

Ed Bartels, P.E., L.S., assistant county engineer for Johnson County, Iowa, calls himself a “drone evangelist,” employing them in a powerful toolkit that includes AutoCAD and GIS.

“We’ve always tried to leverage technology here at the county,” he says. “Like everybody, we don’t have enough money for all the work we would like to do. We’re always looking for ways to be more efficient.”

He adds that small Unmanned Aerial Systems (UASs), often known as “drones,” are a powerful tool delivering a variety of valuable data and information, and are being used more often in infrastructure projects. The air vehicles don’t carry a human operator but are remotely piloted or flown autonomously and also are referred to as Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) and Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems (RPASs).

Shaun Passley, ZenaDrone chairman and CEO, notes drone technology can be applied to all infrastructure projects, providing greater project oversight and visibility, improved project efficiency, reduced cost-overrun risk, better and faster decision making, easy integration with existing solutions such as AutoCAD and simple data visualization tools, and can be accessed and used by anyone on the team.

“Time is key in construction projects,” says Passley. Drone use “provides an unparalleled record of all activities, cuts planning and survey costs, increases efficiency and accuracy, and eliminates disputes over the status of a project at a given point in time,” he adds.

Woolpert is a leading and pioneering firm in providing UAS services. In 2011, the company was doing UAS research for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and in 2013 became the first surveying and mapping company to get a 333 exemption, an airworthiness certificate to operate aircraft without a pilot on board, notes Aaron Lawrence, GISP, a Woolpert senior associate and team leader for Research/GIS/Unmanned Systems. The company has broadened its UAS efforts to encompass more applications, ranging from building inspections to topographic surveying.

Currently, much of the firm’s UAS work is for the FAA, particularly airport applications such as foreign object debris detection on runways, assessing pavement conditions, identifying wildlife and examining airport security. Woolpert also does a lot of monitoring at oil and gas fields, well pads and electric infrastructure.

Landslide detection and mitigation has become a recent focus at the request of municipalities and state transportation departments, notes Lawrence, adding drone use replaces the traditional approach of rappelling. A 3D model can be constructed, and the site can later be examined to calculate any further movement.

Jose Giraldo, DroneBase general manager for property and channel partnerships, notes that “as drones have become cheaper and more sophisticated, companies have seen they can get better data faster and more safely by using a drone than by sending a person climbing up a tower or a building hunting for defects with only their eyes.”

DroneBase specializes in providing full-service inspections—including highly detailed actionable reports—for the wind and solar industries as well as construction, insurance, real estate and property-management companies. The company’s recent acquisition of Inspection2 expanded its services to telecommunications, transmission and distribution inspections.

Solar companies, for instance, employ drones to inspect a solar farm and provide specific actions based on collected data to create a critical repair prioritization list.

“A real estate, construction or insurance company might hire us to inspect a single roof or all the roofs in a business park,” says Giraldo, adding the high-resolution images can be used with artificial intelligence (AI)/machine learning (ML) algorithms to identify the anomalies needing attention. “DroneBase customers like having confidence in enforceable data that can’t be tampered with or accidentally left out.”

Gary Strack, vice president at Anderson Engineering in Kansas City, uses drones for water, wastewater, stormwater, roads, bridges, structural and survey projects to collect time-stamped aerial photography.

Adam Gebhart, senior engineering technician II for Johnson County and a licensed Part 107 pilot, uses a UAS in various forms of infrastructure inspection. (Ed Bartels)

Safety

In terms of safety, in addition to landslide inspection, drones are widely used to keep workers off of roofs, ladders and scaffolding as much as possible to avoid worker injuries.

“Drones with highly sophisticated sensors can more effectively identify things that the naked eye cannot, such as thermal sensors and heat signatures,” notes Giraldo, adding it’s a “win-win for safety and data.”

“There are a number of injuries every year from ladder falls,” adds Lawrence, adding some jobs call for building designers to use ladders to access roofs to examine old HVAC systems.

Some of the company’s southern U.S. clients need fence lines examined, with some of those lines running through a swamp. Lawrence cites a stormwater project in Georgia where it’s common to encounter snakes and alligators. In that instance, a drone can provide better perspective and more data in a safer environment.

Gaining Efficiencies

Bartels notes that as an engineer, having a base map is always the beginning of any design. Until the introduction of UAS, that meant sending out a survey crew.

“Once we started getting countywide aerial photography, I was able to do some of my designs without having to send out a survey crew,” notes Bartels. “I could take the picture they captured from the sky. The resolution wasn’t very good, but you can tell where the road was. A lot of the linework is basically done for you, which saves the county a lot of money and effort from having a crew finding the edge of the road.”

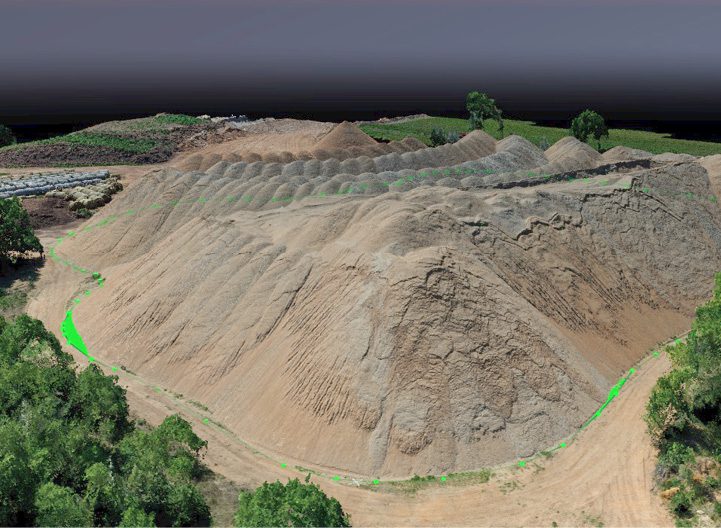

To verify the volume of a stockpile of crushed rock matched what a vendor stated was delivered, Ed Bartels, assistant county engineer for Johnson County, Iowa, used UAS and photogrammetry techniques.(Ed Bartels)

Drones now allow his department to do flights whenever desired to gather real-time data in a matter of minutes rather than waiting for several years for new countywide aerial photography.

“The economy of it really drove it for us,” adds Bartels. “Being a county engineer and a dual-licensed surveyor and engineer, we’re tech people who really know what we’re doing with the computers. Making all these different parts come together, we’re able to streamline our workflows.”

In addition to the drone pilot, there’s a spotter also watching the aircraft and someone working crowd control.

“Rather than needing a full day or week of good weather to collect all this data, I just need 20 minutes in an afternoon, or four hours on a couple of days whenever the weather clears up—just enough to get it done,” says Bartels. “The rest of the time is spent inside.”

Lawrence concurs that drones offer time efficiencies.

“We do some construction monitoring,” he says. “If we do a traditional topography survey with a three- or four-person crew on 1,000 acres, it would take us days, potentially weeks. Whereas we can let a drone fly those 1,000 acres in a couple of hours, bring that back to the office, do a lot of the legwork, and then send the survey crew out to pick up where there is some missing data or information that was unclear.

“If you want to do change detection on a construction project, you fly it before the construction begins,” explains Lawrence. “They dig some trenches, you fly it again. They put the infrastructure in the ground, then you fly it. They bury it, you fly it again.”

That creates a digital record of the history of the construction and helps with contract management.

With regard to a gas main or water main break, Lawrence notes that many times “you see on the roads where they dug the entire road because they didn’t know exactly where that pipe was. With digital construction monitoring, you’re going to see those patches shrink. They close down one lane or that goes down to a 6-foot section. They know exactly where it is, because they have a digital record of it.”

FAA Loosening Drone Regulations

“Currently, we’re limited to 400 feet,” explains Aaron Lawrence, GISP, a Woolpert senior associate. “And you can’t fly over people, who are called ‘non-participants’ in the rules. That is loosening up, and when that happens, you’re going to see a lot more use cases open up.”

The FAA states that certified remote pilots—including commercial operators—who have a small drone less than 55 pounds can fly for work or business by following the Part 107 guidelines. The FAA indicates three basic steps for doing so.

The first is to know the rules, which are delineated on its website in the 14 CFR Part 107 Small Unmanned Aircraft Systems section.

The second step is becoming an FAA-certified drone pilot by passing the knowledge test. Those eligible for a remote pilot certificate must be at least 16 years old; able to read, write, speak and understand English; and be in a physical and mental condition to safely fly a UAS. To study for the knowledge test, the FAA provides suggested study materials. Candidates must obtain an FAA Tracking Number (FTN), create an Integrated Airman Certification and Rating Application profile prior to registering for the knowledge test, schedule an appointment, and take the test. Those who pass their test can register for a remote pilot certificate.

The third step is to register the drone with the FAA.

The FAA Operations Over People rule became effective on April 21, 2021. Drone pilots operating under Part 107 may fly at night, over people and moving vehicles without a waiver as long as they meet the requirements defined in the rule. Airspace authorizations are still required for night operations in controlled airspace under 400 feet, the FAA notes.

Helping With Compliance

The drone also is helpful in meeting compliance issues, Bartels notes. “We have compliance for stormwater management. You need your silt fences up and your countermeasures to make sure that silt is not leaving your site. A lot of times, it’s pretty swampy around the edge, so you’ve got to walk through a foot or two of water. I can send a drone to look at that fence and get up within a couple of feet of it,” he explains.

“Every regulatory update also helps expand use cases and lower the barrier to entry,” Giraldo adds.

Challenges and Resistance

Weather is a primary challenge to using drones, as Bartels notes a drone can only be flown on days that aren’t rainy or windy. According to Passley, other common challenges include security, hijacking, safety and identification, adding there are laws and regulations to prevent and counteract drone security risks and threats. Several governments, including the United States, require drone owners to obtain official UAV licenses before they can operate their drones.

“It’s important to keep up with drone regulations to avoid fines and possible criminal liability,” adds Passley.

Lawrence warns of resistance to companies using drones. “You have the history of doing things the way you’ve always done them, so it’s a technology implementation,” he points out.

According to Lawrence, drones also received negative press when someone wasn’t using them in an appropriate fashion, but that’s slowly but surely changing. Bartels seeks to mitigate pushback through education.

“I tell someone who wants to do topography the ‘old school’ way to ‘go out on that 100-degree day, and I’ll see you eight hours from now drenched in sweat and covered with bug bites.’ You have the sun-exposure risks, and if you’re walking along the side of a road, you’re exposed to high-speed traffic,” he adds.

“Most of my guys are thrilled about [using drones],” notes Bartels. “I have guys volunteering to get their pilot’s license because it’s also kind of fun. Where else are you going to get paid to operate a little remote-control vehicle?”

Another county turned to Ed Bartels, assistant county engineer for Johnson County, Iowa, for a 3D terrain model of a bridge site to verify they met U.S. Army Corps of Engineers requirements. (Ed Bartels)

Some pushback comes from the public, who may be suspicious of a small flying object in their view. To mitigate such hesitation, Bartels has his other licensed pilot onsite fly the drone while he provides education on the drone’s benefits, including saving taxpayer dollars, adding that it usually doesn’t take long to overcome most of the pushback.

Sometimes there are privacy concerns from people wanting to know why the county is flying a drone over their property.

“They don’t realize there are airplanes flying over them all the time,” notes Bartels. “Once you explain to somebody we’re licensed to do this, we’re not doing anything untoward with it, and we’re going to screen out any data we collect that might be personal in nature before we publish it, most people don’t really mind.

“I’ve had a couple people threaten to shoot it down, but once I explained what we’re doing and why we’re doing it, they say ‘that’s really cool,’” he adds. “One of the nice things about being a remote pilot is I can actually turn the control of that drone over to somebody else as long as I’m able to take control if necessary. That will usually get past even the strongest unbelievers—letting them fly the thing for a little bit and just seeing what the drone sees.”

Replacing Human Labor

Addressing a concern about drones replacing humans’ jobs, Lawrence notes that “if we can get this person trained on how to use a drone, it’s potentially going to help them do their job better.”

At a time when factors such as the Great Resignation have affected the ability to keep an operation fully staffed, Passley says, drones have offered the efficiency and benefit of eliminating potential human error and decreasing the overall time it takes to capture critical data for reports.

Inhouse and Subcontracted Drone Work

According to Lawrence, there’s a lot more to buying and flying a drone than people realize, adding Woolpert’s 12 years in this industry sector sets the company up as an authority to help others build up their programs. For those desiring training to run their own program, flying the drone is the easy part.

“A lot of these systems fly themselves,” he points out. “You build an automated flight plan. You have somebody make sure no other aircraft are coming through, and, if they do, they know how to land it safely. The more-difficult part is the flight planning, making sure you’re going to get the data you expect and dealing with the FAA in understanding the regulations. There’s a lot of writing and project planning to have a successful program.”

There also are many levels of sophistication of the drones themselves. “How do you put it together? What sort of sensor or payload are you going to put on it? Is it a laser scanner, a lidar system or a high-resolution camera?” adds Lawrence.

Bartels advises others incorporating drones into their work to start small.

“You can buy a very cheap drone for $500 or $600 that will give you many of the advantages,” he says. “Even an inexpensive drone can lead to a big financial payoff right off the bat, and you don’t really need training. All you have to do is get the drone up in the air, take a few pictures, and be able to download and distribute the pictures of what the drone saw. That’s valuable all by itself.”

Bartels notes that those who want to capture data at a better accuracy may have to upgrade their camera or get a slightly larger drone to carry a bigger payload. He works with entities that prefer to fly drones with their own equipment but don’t have someone to do the data reduction, so they subcontract that part of the work.

Giraldo notes that with many drones being affordable, “it’s less the cost of the drone itself and more the cost of sensors, experienced pilots, and the ability to analyze and act on the data acquired.”

These costs are a major reason for companies to contract such work to industry experts, who often also provide training. As an additional resource, the American Public Works Association (APWA) offers a host of webinars and education sessions on the use of UAVs on topics such as bridge inspections and sewer surveys. Beginner courses include an explanation of different UAV models, how to purchase a new system, safety guidelines and preflight checklists. In-depth UAV courses should address pilot responsibilities, air space, aviation weather, pre-flight inspections, flying without GPS and flying to simulate a bridge inspection.

Artificial Intelligence Here To Stay

According to Passley, the potential applications of ML and AI in construction are vast.

“AI in construction will prevent cost overruns and is used for better design of buildings through generative design, risk mitigation, project planning, improved jobsite productivity, construction safety, labor shortages, and ‘big data’ in construction and post construction,” he adds. “Leaders at construction companies should prioritize investment based on areas where AI can have the most impact on their company’s unique needs. Early movers will set the direction of the industry and benefit in the short and long term.”

“We are seeing AI and ML become more of a hot topic as enterprises look to streamline their workflows and find efficiencies,” says Giraldo.

About Carol Brzozowski

Carol Brzozowski is a freelance journalist specializing in technology, resource management and construction topics; email: [email protected].