Green Roofs: A Growing Trend for a Growing Need

The green-roof industry has steadily grown 10 to 15 percent annually, notes Steven Peck, president of Green Roofs for Healthy Cities (GRHC), the North American industry association for the green roof and wall sectors.

More policy support is in place as many cities mandate green roofs, particularly on new buildings, as decision makers recognize that roof space is an asset. Mandatory requirements for green roofs have been passed in New York City; San Francisco; Cambridge, Mass.; and Portland, Ore., with a number of incentive and grant programs in place for existing buildings.

Stormwater retention is one of the main environmental benefits of green roofs. “It’s been a driver in many cities; it’s very easy to quantify,” notes Peck. “If you keep a gallon of stormwater out of the system, you can actually put a monetary value on that.”

That value is derived through the plants, growing media, drainage layer and moisture retention fleece, all of which increase the green roof’s capacity to retain water. Green roofs provide carbon sequestration, greenhouse-gas emission reduction, air- and water-quality improvements, and support of biodiversity, “which we need to survive as a species,” adds Peck.

Also, green roofs designed to be accessible or even visually accessible provide mental and physical well-being benefits. Peck notes hospital case studies demonstrating more rapid rates of healing with less medicine for patients who can look out their window onto green space. Other research indicates greater staff retention when employees have a place to go to relax.

“Being in the presence of green space is really good for us,” says Peck. “It lowers our stress levels. It improves our mental clarity. There’s a huge science studying the impact of natural settings on human bodies.”

Biophilic design incorporates natural light, wind, green space and open spaces, offering economic benefits to building owners who can get higher rents per unit because of accessible green roofs.

“The amount of money they make outstrips the green-roof costs, so there’s a positive return on investment because people will pay more to have accessible green space where they work or live,” adds Peck.

The blue-green roof—a combination of a cistern and green roof—has emerged in recent years. This roof offers water-storage capacity for controlled-release detention control, combined with the benefits of a green roof.

“The green roof is on the top,” explains Peck. “When the green roof hits its moisture retention capability during a major storm, you have backup detention capacity built in underneath it. That provides another measure of control and certainty in terms of stormwater management.”

From a client-facing perspective, significant benefits differentiating green roofs from other types of stormwater management justify the expenditure: in addition to holding 1 to 3 inches of stormwater, they also support gardening, biodiversity and have aesthetic value. Although green roofs tend to be more expensive on a per-gallon basis, the roof membrane lasts twice as long and reduces energy consumption within a building.

Green Walls and Ecoroofs

Also becoming a popular design choice are green walls (or facades) in which vines and climbing plants or cascading ground covers grow into supporting structures. Living wall systems are pre-vegetated panels, modules, planted blankets or bags affixed to the building envelope. Retaining living walls are engineered living structures designed to stabilize a slope, while supporting vegetation contained in their structure.

Casey Cunningham, City of Portland Bureau of Environmental Services

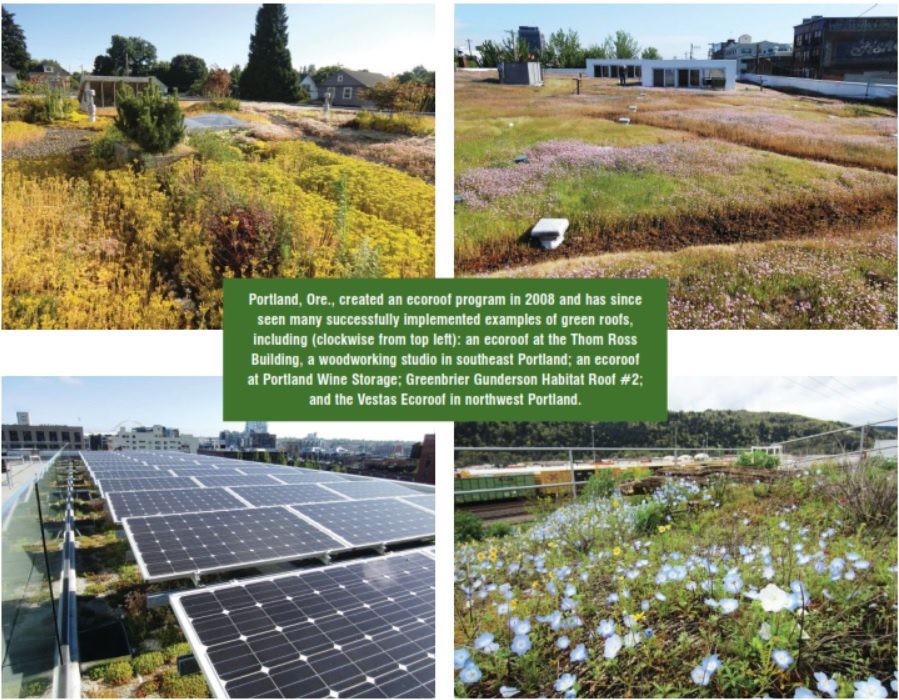

In Oregon, Portland’s ecoroof program was created in 2008 to promote the technology for stormwater management and its multiple simultaneous benefits as well as spur the local industry, notes Casey Cunningham, landscape architect, LEED AP, integrated planning for Portland’s Bureau of Environmental Services.

“Monitoring of previous pilot projects showed ecoroofs do an excellent job at reducing stormwater peak-flow rates and volumes while filtering runoff, and became part of the suite of options in the city’s stormwater management manual for new and redevelopment in 1999,” explains Cunningham.

The program consisted of an incentive grant, outreach and education, technical assistance, policy development, research, and monitoring. It ended in 2013 when the city began work on an ecoroof requirement that went into effect in 2018 on new buildings more than 20,000 square feet in the Central City. Portland has promoted ecoroofs for their multiple benefits.

“They clean, slow or retain runoff, which has downstream benefits for erosion and temperature reduction, and on aquatic habitats,” says Cunningham. “They cool and improve air quality, absorb carbon, and create greenspace and urban habitat, particularly for pollinators. They also provide energy savings and long-term cost savings by protecting the roof membrane from UV light, which extends its lifetime.”

With a wide range of design approaches and costs, decisions should be based on project expectations and goals, notes Cunningham. That includes low-tech DIY built-up systems requiring time for plant establishment. At the other end of the spectrum are all-in-one systems with redundant layers that are lush immediately at installation.

Engineers desiring to reduce costs while still maintaining the benefits of ecoroofs should consider the following:

• Is metal separation really needed?

• Are concrete paver paths necessary given that plants can bounce back from minor foot traffic?

• Is an irrigation system and its maintenance necessary, or can the roof be “topped” with seed or cuttings after a dry summer?

“Volunteer vegetation” will get on the roof, so diligence and amount of maintenance determines the plant community and look over time, but it should manage stormwater well regardless, says Cunningham.

The ecoroof program proved popular, with nearly $2 million in grants awarded to help fund more than 130 projects during the five years the program existed, managing an average of 4.4 million gallons of stormwater annually. Since then, annual acreage installed in the city has continued on a steady upward trajectory as the grant program spurred adoption of ecoroofs as a viable stormwater-management option.

Ecoroofs are an excellent tool for municipalities in certain situations, such as sites that have limited room on the ground for stormwater management, or in combined sewer basins where peak-flow reduction is a major goal.

The District House condo building in Oak Park, Ill., features several ecological amenities, including five green-roof terraces for premium second-floor units.

Room for Experimentation

“In our area, native wildflowers and bulbs have performed well, but those plants look brown or absent most of the year, so combining them with the typical succulents seen on ecoroofs can help ensure year-round greenery while providing diversification,” says Cunningham. “Cacti and other desert-adapted vegetation would likely provide a broader palette of plant options, particularly if there’s an advocate maintaining the roof to reduce competition from encroaching urban weeds.”

“As green roofs have grown in popularity, so has the value they add to construction projects,” notes Sam Irwin, director of business development for Omni Ecosystems, a Chicago-based green infrastructure company that won GRHC honors for its green-roof projects at the McDonald’s Chicago headquarters as well as a multi-residential unit.

District House, a 28-unit luxury condo building in the historic district of Oak Park, Ill., features several state-of-the-art ecological amenities, including five green-roof terraces for premium second-floor units. Units with private green terraces—with an average additional construction cost of $20,000 more per unit—sold for an average of $69,000 more.

“This was a tangible way to see that adding green infrastructure provides return on investment while also increasing the appeal and enjoyment to the resident,” notes Irwin.

On the green-roof project at the McDonald’s headquarters in Chicago, Omni Ecosystems maximized the growing media depth and designed its composition to boost stormwater management. Sixteen months after construction, the green roof managed nearly 1 million gallons of rainfall, releasing no stormwater to the municipal system.

Irwin touts the environmental benefits of green roofs: cooling the surrounding area, reducing the Urban Heat Island effect and amount of dust in the air, absorbing noise pollution, and reducing floods and overflows.

Irwin echoes the observation that numerous cities now offer incentives for integrating green roofs into buildings while others legally mandate their inclusion in new construction. Even without mandates, Irwin notes an increased desire for building owners to have green roofs.

“Outdoor space has long been a popular amenity, but in the COVID-19 era, it is even more sought after as people avoid gathering in public places,” he adds. “Private outdoor spaces like green roofs and terraces provide respite and an opportunity to experience nature while allowing neighbors to maintain social distancing.”

Weight can be a factor on older buildings when designing green roofs, says Irwin, adding Omni addressed that by creating a light and biologically diverse green roof.

For 10 years, GRHC has offered Green Roof Professional (GRP) training and accreditation through a certification program for green-roof designers that has certified thousands of professionals. Continuing Education Units must be maintained to sustain the accreditation.

“GRPs are good people to have working with you on a green-roof project because they understand all the elements that go into designing a green roof,” notes Peck. “There are structural-loading requirements and drainage and irrigation components that have to be understood because some green roofs require supplemental irrigation.”

Although GRP certification covers design, installation and maintenance, the same company isn’t always hired to perform all three functions.

“The key is to get a company that will build the green roof and also maintain it,” says Peck. “The minimum maintenance standard we promote is a five-year contract, because two years—what some members of the industry call the establishment period—is not enough.

“It’s good to have the company that installs the green roof also be the company that maintains it, because they have a greater interest in a high-quality installation if they have to maintain the green roof afterward,” he adds.

There’s also been an expansion of using rooftops for food production with many rooftop farms established throughout North America.

Sixteen months after construction, the green roof of the McDonald’s headquarters in Chicago managed nearly 1 million gallons of rainfall, releasing no stormwater to the municipal system. Image: Omni

GRHC also offers the Living Architecture Academy (livingarchitectureacademy.com) through which it provides free and paid training information on design, installation and maintenance practices. The Living Architecture Performance Tool is available through GRHC’s charitable sister organization, Green Infrastructure Foundation (greeninfrastructurefoundation.org).

The tool is a list of all of the benefits that can be obtained through various green roof and wall designs. An independent rating system similar to LEED enables contractors to apply and submit documentation for third-party review to have a project certified on different levels, depending on the number of credits.

Green infrastructure policy varies with community needs. In North America, there are a number of ways in which green infrastructure policies are executed:

• Density/floor area ratio bonus, in which builders are permitted to increase building density by increasing the height of the building or floor area ratio when green infrastructure is added to the building.

• Grant and rebate funding for specific types of green infrastructure installations.

• Subsidies for property owners who make co-payments for part of the cost of the green infrastructure installment.

• Mandates requiring green roofs under specific circumstances.

• Residential stewardship programs offering financial incentives and technical support to property owners who voluntarily install and/or maintain green infrastructure and stormwater management techniques.

• Stormwater fee credits.

• Tax credits/abatements.

Green Roof and Wall Policy in North America, Regulations, Incentives and Best Practices (2019) can be found at greenroofs.org/policy-resources.

Mounting evidence shows that access to green space can increase concentration and decrease stress as well as provide positive impacts on psychological well-being and overall health.

“As building managers and owners look ahead to a post-pandemic world, they are faced with the challenge of providing a safe and clean environment,” adds Irwin. “Green roofs provide the potential to go even further by enhancing the health of its occupants.”

Green roofs not only provide an ROI and health benefits, but also social and economic benefits, particularly in urban areas through improving the environment, increasing property values and enhancing the social fabric.

“We believe that integrating natural and dynamic landscapes into the places we live and work is a fundamental building block of resilient cities, and healthier and happier humans,” adds Irwin.

About Carol Brzozowski

Carol Brzozowski is a freelance journalist specializing in technology, resource management and construction topics; email: [email protected].