Making Everyone Happy: Early and Effective Collaboration to Realize a Beautiful Building

Structural engineers occupy a difficult niche in high-rise construction; too often, their role is perceived as a “reality check” on the actual cost-effective constructability of beautiful, ambitious buildings. This perception can bring them into sometimes bitter conflict with architects, developers and contractors, but Josh Dortzbach, principal at Chicago’s Forefront Structural Engineers, doesn’t see it that way.

“Basically, our job as structural engineers is to be the ‘bones’ of the building and to work collaboratively with the architect and other stakeholders so that the ‘flesh’ looks beautiful and everything is working together to make the building stand up,” says Dortzbach. “Our most-enjoyable work is when there’s an iterative process with the architect in that process so we can collaborate on efficiency for systems that make their way into the architecture.”

“Collaboration” and “iteration” are common buzzwords in the world of statement architecture, but Forefront has more than backed up that easy talk with excellent work on dozens of quickly iconic buildings in Chicago’s metro area, including the Viceroy Hotel (an 18-story glass tower named one of the Top 10 hotels in the United States by Condé Nast Traveler), the New Albion at Oak Park (the 19-story building’s innovative “stepped” design helped win approval for what’s now one of Oak Park’s tallest mixed-use luxury residential developments), and Northeastern Illinois University’s El Centro building (a “boldly sculpted academic structure,” according to Blair Kamin of the Chicago Tribune).

Forefront’s reputation for early, iterative and authoritative collaboration is being tested and confirmed on one of the firm’s current projects: a 17-story office tower planned at 167 N. Green Street in Chicago’s Fulton Market district.

Architect: Gensler

Developer: FOCUS Development and Shapack Partners

Contractor: FOCUS Construction (General Contractor)

Structural team and firm: Forefront Structural Engineers: Steve Franckowiak, Associate; Amanda Featherstone, Project Engineer; Josh Dortzbach, Principal

Steel supplier: Lenex Steel

Steel erector: Danny’s Construction

Concrete core: Tribco Construction Software

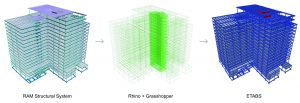

a. Design Software: RAM Steel, ETABS, Excel, RHINO+Grasshopper

b. Modeling software: Autodesk REVIT 2017

Public Space

167 N. Green Street is a block smack dab in the middle of the Fulton Market district in Chicago’s West Loop, and it’s fair to call the district Chicago’s hottest and trendiest at the moment. Zoning changes and several major developments (including the Google Chicago headquarters Forefront designed as a conversion from a 100-year-old cold-storage facility) are contributing to a major transformation from a gritty meat-packing, warehouse and industrial district to a technology center with luxury residences and all the ancillary hotels, bars, restaurants and retail space.

This puts a lot of pressure on any new development in Fulton Market (usually from the city or community groups), but, in this case, the developer insisted on a pedestrian-friendly feature. “This building will take up about 3/4 of the block, and most designs for this type of space call for some parking and enclosed retail space on the entire first floor,” explains Forefront Associate Steve Franckowiak. “Here, the developer actually called for a challenging design feature that added public space. They’re calling it the ‘Mews,’ and it’s a 50-foot-wide, 40-foot-high passage through the middle of the building connecting the very hip Green Street to Halsted Street, Fulton Market’s most active corridor.”

Incorporating more public space in large developments is a laudable goal, but it did create challenges for Forefront. For example, the structural engineering team was forced to look closely at the six columns supporting the 40-foot clear space that lends so much drama and usability to this new building—since they would now be publicly viewed, there was a need for good aesthetics, and since the 40-foot slender columns would need to support the tower above, there were construction difficulties to consider.

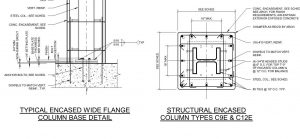

“For aesthetics, we eventually recommended concrete-encased composite-steel columns for this space, rather than traditional steel, because the finished look will be much more in keeping with the architect’s vision,” says Franckowiak. “That decision worked for the architect and developer, and was structurally sound and cost-effective. It also decreased the weight of the columns down to about 500 pounds per lineal foot, along with staging issues during construction, so we had to take a careful look at just how these columns would be delivered and craned into place. It was very satisfying to come up with a solution that could be built and worked for everyone, including the community.”

Digital renderings focus on the “Mews,” a 50-foot-wide, 40-foot-high passage through the middle of the building.

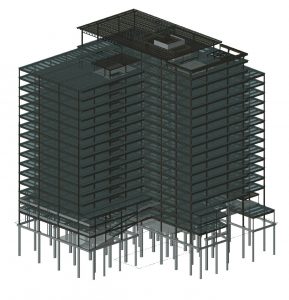

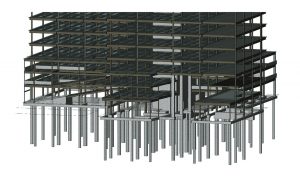

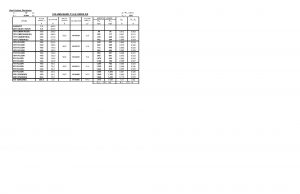

Isometric views of REVIT models show 3D coordination with structural, architectural and mechanical requirements (top); the lower podium highlighting structural composite columns with concrete encasement used to maintain a slender profile (middle); and integrated ramps for lower parking levels at the base of the building (bottom).

Maximizing Ceiling Height

Another project challenge was more traditional: maximizing ceiling heights to gain the most desirable floor space possible within the total building envelope. “To do this, we had to minimize floor sandwich thicknesses,” says Project Engineer Amanda Featherstone. “The architect pushed us pretty hard to get them down to a certain size so they could have maximum height within their space, but that required us to coordinate a lot with the mechanical trades so they could penetrate through our beams. There was a lot of back-and-forth coordination among all teams on the job.”

One factor that was a major help with this intense collaboration was the early sharing of building information modeling (BIM). “We all shared our models—structural, plumbing, mechanical, architectural—with all the trades from the get-go, and it certainly helped,” adds Featherstone. “But there were still challenges, including pricing, since the mechanical trades tend to be design-build. We worked out a lot of issues, and we’re still working them out as we head into construction.”

By using inhouse parametric programming, RAM structural analysis software was optimized for steel framing, and ETABS was optimized for lateral load and concrete core performance.

In the scale of large commercial infrastructure, floor thicknesses and mechanical details can be termed “micro.” But during this early collaboration on floor thickness, Forefront also found ways to make “macro” adjustments that would optimize ceiling heights.

“One of the bigger adjustments had to do with the efficiency of the vertical system of the building,” notes Dortzbach. “This is a reinforced concrete core wall system for the vertical support of the building, elevators and stairs, which also acts as a spine for the building for wind loads. Early collaboration with the trades helped us bring together their vertical risers in one spot that made all that work more efficient for everyone. Early collaboration also helped us see that the core for the building needed to be optimized so it was big enough to take the entire building, but not so big that it would eat into precious real estate space—there were a lot of conversations about that, which led to big changes.”

According to Dortzbach, “The schematic design and construction administration phases are the two most important design services of a project, because you need to make smart decisions upfront and execute the decision on the back. This decision about the core allowed everything to come to one spot, and we made it early enough to work with the architect effectively. For example, they were willing to align the stairs with elevator shafts and mechanical shafts, and that made the whole building better.”

Another developer decision that affected ceiling heights was the “Amenity Penthouse:” the suite of conference and event spaces, public gym, gardens and basketball court slated for 167 N. Green’s top floor. Like the Mews, the Amenity Penthouse increases community use of the building and adds to public space. But also like the Mews, this laudable use of space had the potential to negatively affect the project’s commercial viability.

Plans show the typical detail of structural encased hybrid steel-concrete columns.

“The top of the building is where the views are, of course, so the top floor is the most desirable and highest rent space,” explains Dortzbach. “Putting a gymnasium and a dual-purpose event space right on top of that makes vibration and sound mitigation a challenge. So we had to think carefully about that and find ways to stiffen the floor sufficiently to mitigate vibration but also not be cost-prohibitive.”

Most strategies for sound and vibration mitigation would start with stronger or deeper beams, but this would necessarily increase floor sandwich thickness and cut into top-floor ceiling height. Instead, Forefront found a way to use topping slabs to dampen vibration—and thus sound—without undue increase in floor thickness. This approach also provided a better gymnasium floor and was lighter overall.

Inhouse spreadsheets were used to determine steel-column shortening relative to concrete-core shortening as well as concrete-core shortening due to concrete mix design, shrinkage and strain.

It was still tricky to get the correct solution. “We used a lightweight concrete topping instead of normal-weight concrete, so we didn’t have to transfer as much load down to the foundation,” explains Franckowiak. “But at the same time, a lighter-weight system can make vibrations higher frequency and a bit more challenging, especially in a building like this with long clear spans.”

The end result proved to be an excellent example of how structural engineers can make everyone happy when they view their work as an “iterative process” that prioritizes collaboration with the view of realizing “efficient (structural) systems that make their way into the architecture.” In this particular case, iteratively “sweating the details” of concrete weight, topping slab stiffness, and floor sandwich thickness led to a solution that provides a good foundation for the Amenity Penthouse (and its basketball court) with minimal reduction of top-floor ceiling height and no effect on “leasability.”

Everything in Balance

At 17 stories, 167 N. Green is not especially tall for a Chicago high-rise. But it will be one of the taller buildings in the West Loop, and inclusion of the large Mews space and the slightly L-shaped footprint complicates basic structural issues to the point where differential shortening had to be considered.

“In buildings with a concrete core and steel framing like this one, steel columns can shorten under load more than the concrete core, and that can lead to sagging floors,” says Franckowiak. “It’s usually not a problem with buildings under 50 stories, but with the unusual features here—and in response to contractor concerns—we felt we really had to pay attention to this factor and be able to validate our conclusions.”

That validation fell to Featherstone, who created her own analytical tool to explore and validate Forefront’s structural support decisions. “My favorite go-to for tasks like this is to use Excel and create a program purpose-built for particular projects,” she says. “Here I incorporated the different standard formulas—from design guides—for steel column shortening and concrete wall shortening, and was able to verify that differential shortening would not be a factor.”

The work led to some changes, such as more use of concrete-encased columns, but it basically confirmed that the emphasis on steel support was warranted for this building. All told, about 5,500 tons of steel will be used to hold the building up, hopefully for centuries, and “that’s not a small number,” according to Dortzbach. Neither is it a small expense.

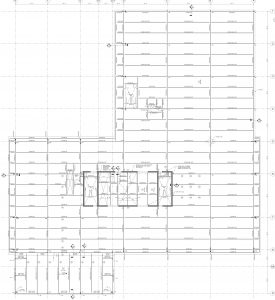

Floor plan shows the first floor/ foundation plan with the centrally located concrete core system.

“Most of the steel support here was designed and specified before tariffs and other economic issues began to affect steel prices,” he notes. “Given the way our engineering work has been able to address architect and contractor concerns, while also preserving value for the developer, it’s become apparent that steel is still a viable solution even in a difficult economy.”

Thrilled

“At the end of the day, our job as structural engineers is to make sure this building will stand up over time,” says Dortzbach. “But our job is also to make sure that everyone involved—architect, developer, end users and surrounding neighborhood—is thrilled with what’s accomplished. To do that, we have to think like engineers, but we also have to think like artists and residents. Here, I really think we’ve done that.”

Evidence suggests he’s right. Approvals for this design were obtained with relative ease in Chicago’s contentious community arena, neighborhood response is positive, and the developer is very happy to be realizing a beautiful building that will still offer the “largest floor plate available in Fulton Market with 360-degree views and 13’6” ceiling heights.” Early leasing commitments are strong. This building, and dozens of additional Forefront projects in this region, prove that when structural engineers deliberately seek to work with other stakeholders as collaborators rather than dictators, great buildings happen naturally.

To watch a video created by the development team for the 167 N. Green Street building,visit informedinfrastructure.com/46285/video-chicagos167-green-street/

About Angus Stocking

Angus Stocking is a former licensed land surveyor who has been writing about infrastructure since 2002 and is the producer and host of “Everything is Somewhere,” a podcast covering geospatial topics. Articles have appeared in most major industry trade journals, including CE News, The American Surveyor, Public Works, Roads & Bridges, US Water News, and several dozen more.