New Report Criticizes Validity of EIA Projections

Corvallis, OR — Post Carbon Institute released a report today authored by earth scientist J. David Hughes raising critical doubts about the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s (EIA) projections for domestic oil and shale gas production. The report, “Shale Reality Check: Drilling Into the U.S. Government’s Rosy Projections for Shale Gas & Tight Oil Production Through 2050,” takes aim at the veracity of forecasts found in the Annual Energy Outlook 2017 (AEO2017), in advance of the planned release of the EIA’s AEO2018.

“Shale Reality Check” provides a detailed assessment of the AEO2017 shale gas and tight oil projections, based on an analysis of key fundamentals and assumptions in the plays that make up the majority of the EIA’s projected production of unconventional oil and gas resources. Hughes’ analysis—using comprehensive play-level well production data current through late 2017— finds that the AEO2017 forecasts for most plays are extremely optimistic.

“There is no doubt that the U.S. can produce substantial amounts of shale gas and tight oil over the short- and medium-term,” Hughes noted. “Unrealistic long-term forecasts, however, are a disservice to planning a viable long-term energy strategy. The very high to extremely optimistic EIA projections impart an unjustified level of comfort for long-term energy sustainability.”

Policymakers, investors, and the media rarely consider the quality of Annual Energy Outlook projections, which the EIA’s own retrospective analysis has found to be consistently over-estimated. “Before the media runs with the EIA’s 2018 forecasts for future oil and gas production, or government officials use them to set important energy policy, we encourage them to look behind the curtain of the EIA’s assumptions and ask some hard questions,” said Asher Miller, Post Carbon Institute Executive Director. “One can only assume that the EIA’s optimism is based on technological improvements made over recent years. But as the data show, these improvements have only led to a faster depletion of oil and gas reserves, not a growth in the total amount of oil and gas that can be produced. And we’re already seeing these technological advances and focus on sweet spots hitting the point of diminishing returns in a number of plays.”

Key Takeaways:

- This analysis finds that EIA reference case projections of shale gas and tight oil production through 2050 are highly to extremely optimistic, and are therefore very unlikely to be realized.

- Required production exceeds the EIA’s own estimates of proven reserves plus unproven resources in several plays, and overall assumes that 100% of proven reserves and 60-73% of unproven resources will be recovered by 2050. (Proven reserves have been demonstrated by drilling to be technically and economically recoverable; unproven resources are less certain and thought to be technically recoverable but have not been demonstrated to be economically viable.) Furthermore, the EIA projects that production for most plays will exit 2050 at levels well above current rates, implying that there are vast additional resources remaining to be recovered after 2050.

- Shale plays are not uniform. “Sweet spots” or “core areas” with high productivity reservoir rock occupy a relatively small proportion of most shale plays – usually less than 20%. Drilling in the wake of the mid-2014 decline in oil prices has focused on sweet spots, however drilling locations are finite, and “frac hits” and well interference from drilling wells too close together have already been observed (this reduces production of both the original and infill wells).

- Wells in shale plays decline between 70-90% in the first three years, and field declines without new drilling typically range from 20-40% per year. Therefore, maintaining production requires continuous drilling. As sweet spots are depleted and drilling moves into lower quality reservoir rock, drilling rates and the prices to justify them will have to increase substantially in order to maintain production and/or stem declines.

- Average well productivity has increased in most plays since 2012 as a result of both better technology and “high-grading” plays through focusing drilling on sweet spots. Better technology includes longer horizontal laterals, more fracking stages, and a tripling of water and proppant injection since 2012. Enhanced technology allows each well to access more reservoir rock and produce the resource faster and more economically with fewer wells, but does not necessarily increase the ultimate amount of resource that can be extracted.

- Average well productivity in some counties and plays has declined in 2017. This suggests that technology there has reached the point of diminishing returns. Ultimately technology cannot overcome poor quality reservoir rock, and drilling in these areas suggests that sweet spots are playing out and drilling of necessity is moving into lower quality rock.

- To meet the reference case projections for shale gas and tight oil in its Annual Energy Outlook 2017, more than 1 MILLION wells would need to be drilled in the major plays between 2015-2050, at a cost of $5.7 TRILLION, and an additional 680,000 wells in minor plays, for a total of 1.7 million wells at a total cost of $9.8 trillion. This compares to EIA estimates of 1.3 million wells at a cost of $7.7 trillion for all oil and gas production (including onshore and offshore conventional production). Given the EIA’s overestimates of future production, it is uncertain how many of these wells would be feasible to drill. But considering the energy security implications of overestimating future production, and the environmental implications of drilling so many wells, the US would be well advised to develop an energy plan that doesn’t rely so heavily on extremely optimistic EIA forecasts.

Other Findings:

- The Permian Basin plays are the main driver for tight oil production growth. In Permian plays such as the Wolfcamp and Spraberry, production is increasing rapidly, although Bone Spring production has flat-lined recently.

- All other major tight oil plays are producing at rates below peak levels – the Bakken peaked in 2014 (now down 12%); the Eagle Ford peaked in 2015 (down 34%); the Niobrara peaked in 2015 (down 25%); and the Austin Chalk, an old play being redeveloped with fracking, peaked in 1991.

- The Appalachian plays are the main driver for shale gas production growth—the Marcellus and Utica now account for 48% of U.S. shale gas production. EIA forecasts for the Marcellus and Utica, which project they will provide 52% of cumulative U.S. shale gas production through 2050, are rated as extremely optimistic.

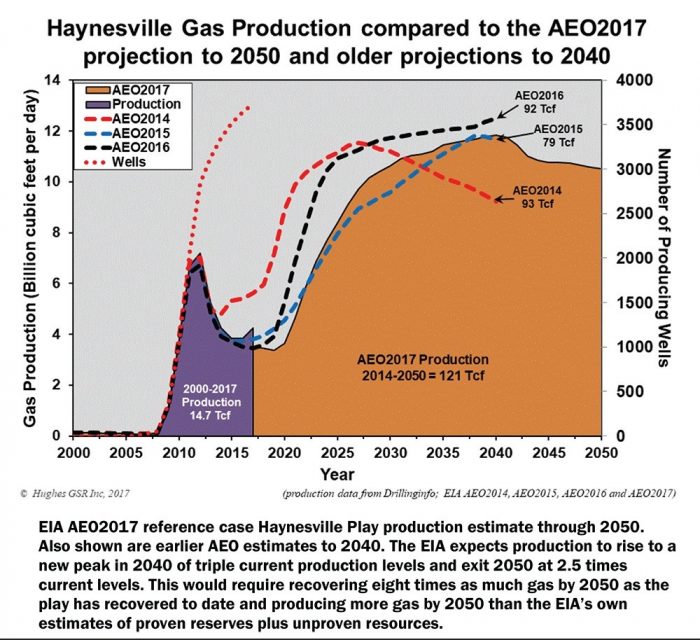

- All other major shale gas plays are producing at rates below peak levels – the Barnett peaked in 2011 (now down 44%); the Haynesville peaked in 2011 (down 44%); the Fayetteville peaked in 2012 (down 44%); and the Woodford peaked in 2016 (down 25%).

EIA estimates of production through 2050 for these plays, most of which assume a revival of post-peak fields with production exiting 2050 well above current production levels, are rated as highly to extremely optimistic based on an analysis of play fundamentals.

Suggested Questions for the EIA:

- Why are the AEO2017 projections for shale gas and tight oil so optimistic?

- Why is there so much difference at the play level between AEO2017, AEO2016, and AEO2015 when play fundamentals have changed little?

- Why does the EIA assume that more than 100% of the sum of proven reserves and unproven resources can be recovered from some plays?

- What is the EIA’s response to analysis of play fundamentals that finds “sweet spots” are limited and although technological improvements allow each well to access more reservoir rock, they don’t necessarily increase the estimated ultimate recovery (EUR) or plays they just allow the resource to be recovered with fewer wells more economically?

Post Carbon Institute envisions a transition to a more resilient, equitable, and sustainable world. We provide individuals and communities with the resources needed to understand and respond to the interrelated ecological, economic, energy, and equity crises of the twenty-first century. Visit postcarbon.org for a full list of fellows, publications, and other educational products.

David Hughes is an earth scientist who has studied the energy resources of Canada for four decades, including 32 years with the Geological Survey of Canada as a scientist and research manager. Hughes is president of Global Sustainability Research, a consultancy dedicated to research on energy and sustainability issues. He is also a board member of Physicians, Scientists & Engineers for Healthy Energy (PSE Healthy Energy) and is a Fellow of Post Carbon Institute. Hughes contributed to Carbon Shift, an anthology edited by Thomas Homer-Dixon on the twin issues of peak energy and climate change, and his work has been featured in Nature, Canadian Business, Bloomberg, USA Today, as well as other popular press, radio, and television