Mexico City Earthquake

Day 1: Death, sadness and mariachi music

I crawl through a bunch of cracked concrete, twisted reinforcing bars and pancaked furniture. Overhead, the concrete deck is getting narrower and narrower as I progress the gap in this collapsed concrete building. The floor above is skewed 45 degrees, with outside light streaming through. The floor essentially collapsed onto this floor. The smell of death is everywhere.

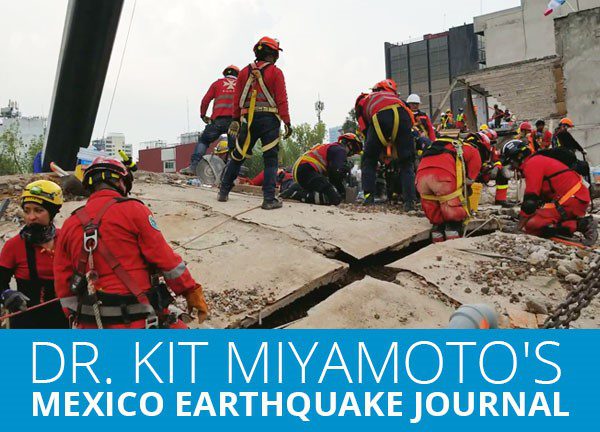

Our team arrived here in Mexico City at 3 am last night (Tuesday) from Costa Rica. We have been scanning through the damaged Condesa neighborhood this morning. It is a nice neighborhood of little cafes and parks. We notice that damages are spotty and not as heavy as I have seen in the past in the 2008 Sichuan or 2011 New Zealand earthquakes. This earthquake was M 7.1, but it was not shallow at 51 km deep with the epicenter 150 km away. This reduced the earthquake energy before it reached this city. Around noon, we entered a cordoned area of a collapsed building. It was a five-story concrete office building now reduced to two stories. The top four levels are pancaked on the second floor. Massive chunks of concrete floor are resting on one level of the structure, which is now supported by an impressive amount of steel shoring. Firefighters, rescue workers and Mexican marines are everywhere. A chief engineer on site requested to meet us.

“We lost 20 people here

and we think 20 bodies are still buried here”

“We lost 20 people here and we think 20 bodies are still buried here,” he explained to us. “We are doing the best we can to get to the bodies, but I want to go through our technical process with you.” He wants to make sure that structural stability exists while his USAR team is in the building amid aftershocks. They are a truly professional bunch; many are volunteers, including the chief engineer. Another engineer tells me: “I actually live three blocks from here and I arrived a day after to this site and have been working here 24/7 since. This is my community, so it’s my duty to help my people.”

We go into the structure to hear how the USAR team intends to make holes to reach the bodies. A Spanish USAR officer yells at me. “Very careful! There is body fluid dripping from the crack above here.” The smell is a combination of dust, concrete and death. It is a smell that will never leave you. Our trusted Mexican chief engineer leads the way to the location he is looking for. Three of us discuss the sequence of the operation. A USAR leader wants to punch a hole from below to get to the bodies faster, but the chief engineer wants to go from the top, which is much safer. They used sensors and search dogs throughout to locate people. No signs of life, very sadly. After six days, they know there is no one living left under this pile.

In the very end, we all agreed on the safer top-down approach. It is a prudent approach to avoid unnecessary risk to USAR lives. We come across more bodies close to collapsed staircases. Many people from this building ran out down these staircases and saved their lives. Some didn’t make it.

“I met a friend who worked here, and he told me he ran to a staircase with two other colleagues when the shaking began,” an engineer tells me. “Two of them turned around to help a lady who fell. But my friend kept running and, last minute, he jumped to the staircase as the building around him was collapsing with tremendous noise and dust.”

We talked about the danger of this type of building, which is pre-1985 nonductile concrete. Mexico City experienced an even more powerful earthquake in 1985 and building regulations changed substantially after that. Old concrete structures are one of the most dangerous building types that exist on earth. Their inadequate reinforcing details make the concrete very brittle under seismic motion. All damaged buildings we saw today were this type. You know how we teach people to duck under a desk during an earthquake? We teach this in California. But if I’m in a nonductile concrete structure, I will run as fast as I can outside and so should everybody.

This earthquake was also different from the 1985 one. The Mexico City earthquake in 1985 was a long-distance earthquake with long, swaying motion. This affected taller structures, six stories and higher. But this earthquake had a much sharper and faster shaking motion, which impacted three- to six-story structures more. It’s what we called “resonance effect.” Every earthquake is different and affects different types of buildings. So, one cannot say that a building is safe if it went through one earthquake. Next one can be totally different. That’s why seismic strengthening is important. It saves lives and it is feasible and cost-effective.

It is getting darker and we say goodbye to our brave rescue workers. Rain is starting to beat on our hardhats. It’s getting cold and wet and I suddenly realize the team has not eaten all day. We find a little hole-in-wall joint and run into it. It’s packed and a mariachi band is playing loud. There’s tequila and beer on every table, it seems. Everyone in the restaurant looks over at us as we enter. They notice our hardhats, headlamps and breathers. Suddenly, people stand up and applaud. This is a total surprise. I’ve had plenty of people thank us for what we do in the past, but I’ve never been in a standing ovation. A big guy with a cowboy hat at the corner table orders three beers for each for us. Our sad memories of the building fade a bit with the cheerfulness and friendly smiles from the Mexican people and the lively Mariachi music.