ONE of the murals depicting the history of Paducah on a wall built to keep out the river shows a captain in his pilot-house, looking over a 15-barge tow with 24,000 tonnes of cargo. At the turn of the last century this small city in Kentucky, at the confluence of the Ohio and Tennessee, became a hub of the inland-waterways system and the home of barge and tugboat companies, dry docks and repair shops. Its Centre for Maritime Education still trains river mariners all over the country.

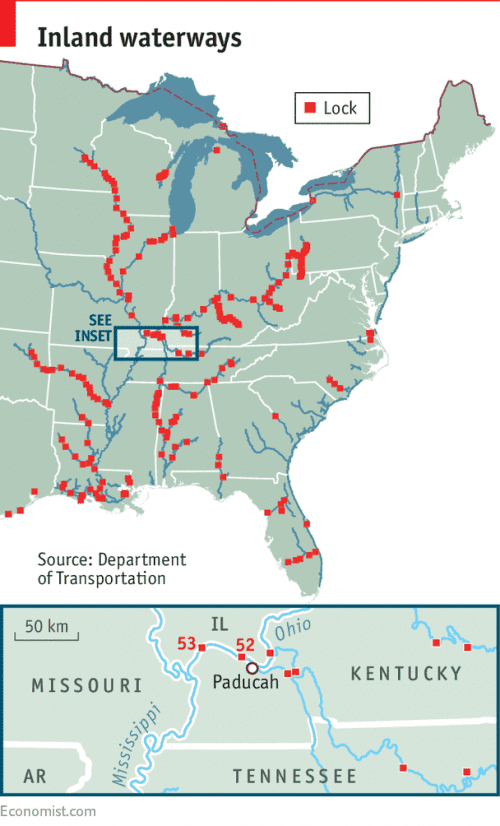

Another mural shows Lock and Dam 52, about 17 miles downstream from Paducah on the Ohio river, which is now an emblem of America’s crumbling river infrastructure. Lock and Dam 52 and 53 are the busiest spots on the inland river-system, a bottleneck through which 135m tonnes of grain, coal, steel, iron, cement and other cargo move every year. Built in 1928 and 1929 by the Army Corps of Engineers, which maintains waterways, they should have been replaced in 1988, as locks have an expected lifespan of about 50 years. In 1988 Congress approved a budget of $775m to replace them within ten years. Almost 30 years later the Olmsted Locks and Dam, which will replace 52 and 53, is still under construction, in part because the Corps, to save money, experimented with building in the wet rather than making the dam in sections on dry land first. Costs have ballooned to more than $3bn; the project is forecast to be operational by 2024.

“Locks 52 and 53 are a huge headache for the shipping community,” says Mike Toohey of the Waterways Council, an advocacy group. On October 9th Lock 52 was closed for the second time since the start of September, leaving 475 vessels stranded in the grain-harvest season (60% of grain exports move by water). Each unscheduled closure of locks costs tens of thousands of dollars as deliveries of goods are delayed and barge captains and other staff are paid for idling on the banks of the Ohio. The total cost of delays at the two locks is an estimated $640m every year.

The stoppages are also hurting the reputation of inland waterways as the best way to move bulky things around. Roughly 600m tonnes of cargo, or 14% of domestic freight, travels on rivers each year. A single barge has the same dry-cargo capacity as 16 railway goods wagons or 70 lorries, and the liquid-cargo capacity of 46 goods wagons or 144 lorries. A 15-barge tow of dry cargo, as on the mural, is equivalent to 216 goods wagons with six locomotives or 1,050 lorries. Barges emit fewer greenhouses gases, use less fuel and cause far fewer deaths and injuries than lorries or trains. They also tend to be farther from population centres, so that any spills or accidents are likely to cause less damage.

Over the past ten years closures of the 239 locks on America’s rivers have increased sevenfold. The infrastructure report card of the American Society of Civil Engineers gave inland waterways a lowly D this year, since half of all vessels had experienced delays across the inland-waterways system. A closure of the Mississippi costs $300m a day, says Colin Wellenkamp of the Mississippi River Cities and Town Initiative, a non-profit organisation. He thinks most locks need an overhaul and some are close to complete failure.

Advocates of river transport hope it will not take the shutdown of a critical lock for months to focus minds on the investments needed to modernise waterways. President Donald Trump is including locks and dams in his grand plan to invest $1trn in infrastructure. In early June, standing on the banks of the muddy Ohio river with a coal barge in the background, he noted the massive underfunding of repairs of the waterways system and remarked that “we simply cannot tolerate a five-day shutdown on a major thoroughfare for American coal, American oil and American steel,” as happened in December on the Ohio near Pittsburgh. He has not revealed details of his proposal, which will probably rely mostly on cash from public-private partnerships, but at least he seems aware of the problem. “It is the first time we had such presidential attention since FDR,” says the Waterways Council’s Mr Toohey, hopefully.