Preparing Today’s Students to Create a Smarter Tomorrow

There is a great deal of buzz in recent years about the concept of “Smarter Cities.” Despite increasing numbers moving to urban areas, there is significant concern that our nation’s infrastructure still ranks woefully behind the rest of the world in terms of quality. With no solid long-term plans to fund required repairs and renovations, much less building the new infrastructure required to support our evolving needs, the conversation is sharply focused on how to do more with less by leveraging technology to innovate the way we design and build the cities and highways of tomorrow.

In considering the future, the conversation naturally connects to our nation’s youth and how we’re preparing up and coming designers and builders to take an interest in the subjects that provide the backbone for design innovation: the sciences, engineering, technology and math (STEM). One of the inherent problems of introducing new technologies and processes to solve large-scale problems is that its success relies on a workforce that is both educated in using those tools and is passionate about solving the issue. Essential pieces of the puzzle include providing students with access to the technology, as well as adequate education and support to ensure that upon graduation they have both the knowledge befitting their degree and a deep understanding of the tools of the trade. After all, even with the best-possible technology to solve our infrastructure challenges, without developing the interest and knowledge of today’s youths, we’ll be no closer to creating smart cities tomorrow.

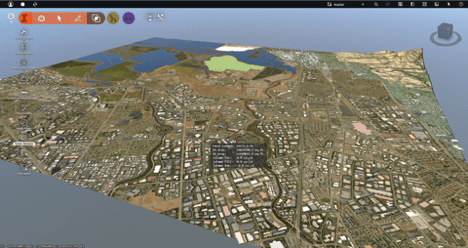

Model of Mountain View, California, created in just 15 minutes by a Columbia University student.

Making Smart Cities a Reality

To help make this a reality, Autodesk has made its software free for students and educators. This is an excellent first step toward addressing the problem of access to the tools. However, there is still the issue of understanding the technologies through and through, and also being motivated to use them. Thankfully, based on a recent visit to Columbia University in New York City, I don’t think motivation is going to remain a problem.

I recently had the opportunity to speak with the students of an urban design class at Columbia and provide an overview of several design and analysis tools, including but not limited to Vasari, GBS and Autodesk InfraWorks 360, which could be beneficial for their class project. While many of their questions were technical and design-process oriented, it was clear that they were not just thinking in terms of “pics and clicks,” but rather had the bigger picture in mind, considering how they could incorporate the technology into their projects in order to solve a problem.

Admittedly, it can sometimes be hard to get excited over technology that you work with all the time. How many people get a thrill out of firing up Microsoft Word? But the excitement these students had when they discovered how the tools could be applied to further the creative process brought them to a new level of thinking. For instance, witnessing how quickly they could create an accurate site of almost any place in the world, and then query it for different kinds of data to assemble a more sustainable design solution, was an eye-opener. In fact, it still is for me too. We have come a long way since I was in school, mastering a laborious process that involved lots of trace and markers to get a feel for things like slope, density and flood plains.

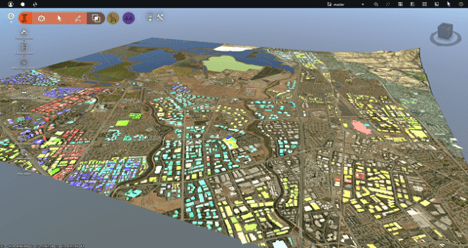

Illustration of applying “themes” to a model in Autodesk InfraWorks 360 to quickly review building heights.

Looking at Today’s Intelligent Tools

Students are at a real advantage now. Today’s tools allow them to spend less time pulling data together from multiple sources, organizing the information, and reworking their designs after testing a potential solution- now they can spend more time on the actual problem. However, don’t mistake this for cheating; we’re not talking about a calculator spitting out answers while removing the work or understanding. We’re looking at more powerful tools that organize information quickly and cleanly, showing you results in an easier to interpret form, like a 3D model.

The students’ project involved the challenge of dealing with sites that are in multiple cities across the globe. In today’s boundary-less world, this is not an uncommon scenario. Thanks to the latest technology, we have the ability to quickly pull together the building blocks of each site using multiple information sources. Add to that the ability to easily collaborate with others on a team spread across disparate locations to generate multiple scenarios, and we can see through the results how much technology innovates the entire design process, allowing the students to focus on solving big problems rather than getting stuck in the minutia.

The Challenge of Building Smarter Cities

When setting out to develop smarter cities, there is an understanding that the goal is not something that will be achieved quickly. It takes time to change the existing environment, and the end goal is something that we know will take hard work and vision to get to. The challenge of building smarter cities is complex. Even a single building is essentially a big machine, with all its different parts, systems and elements involved in a (hopefully) efficient and symbiotic relationship. Combine with that the added complexity of a building’s relationship to the site, as well as the surrounding buildings, and one can start to imagine how the development of whole cities is an immense undertaking. The urban design students at Columbia understood that when an analysis is done on a building or element of a site, it shouldn’t be done in a vacuum; it needs to take into consideration how it relates to the machine as a whole.

Conclusion

With students like these, the future is bright. A future population that “gets it” ensures that not only will they have a better chance at finding employment when they graduate, but ensures that the next generation of designers and engineers have both the tools they need and the critical ability to create a smarter, more sustainable tomorrow.

About Peter Marchese

Peter is a Senior Consultant at Microdesk, specializing in assisting organizations with implementing Building Information Modeling processes. This includes providing on-site assistance, custom content, training and creating goals and roadmaps to integrate technology and workflows into their long term plans. Peter has also assisted companies with understanding and applying new and upcoming technologies with the goal differentiating their skills from competitors by enhancing coordination and visibility with tools such as cloud based services. Prior to joining Microdesk, Peter worked at design firms on residential, institutional, liturgical and commercial projects. He has managed projects throughout all phases, performed field surveys, code and product research, worked on specifications, and presented to approval boards. Finished projects include several laboratory/research buildings, residences, libraries, movie theaters, and a new processing and distribution center for the US Postal Service. Peter holds a Bachelor of Science degree in Architecture from Drexel University in Philadelphia, PA.